Features

Bill See: The Daily Vault Interview

by Jason Warburg

Bill See is a rock and roll lifer.

There was a recent period where the Los Angeles born-and-raised singer-songwriter-guitarist wasn’t sure that was true—a period of retreat and reassessment before, during and after the passing of his single biggest influence, his mother. But after nearly four decades in music—first as frontman for critics’ darlings and late-’80s LA “it” band Divine Weeks, then as a solo artist—See came roaring back from the sidelines with 2025’s Bow To No One, an urgent and emphatic statement of purpose at a tumultuous time for both himself and the country he loves.

Back in the day, Divine Weeks burned brightly through two albums that walked in the footsteps of U2, The Clash, Springsteen and other true believers in the power and majesty of rock and roll. But even as diverging priorities splintered the group’s founding lineup, the moment they had been striving to capitalize on slipped away. Their second album, another collection of earnest, passionate anthems, was released on the same day as Nirvana’s Nevermind. The musical world had changed, and Divine Weeks was a casualty.

In time, See forged onward as a solo artist and eventually tried his hand as an author, turning his journals from the band’s inaugural summer 1987 tour into his 2011 memoir 33 Days: Touring In A Van, Sleeping On Floors, Chasing A Dream. The book is a riveting and revealing chronicle of how that first DIY tour tested and forged both the band and its individual members. The book tour for 33 Days found See reuniting with Divine Weeks co-founder and guitarist Raj Makwana to perform as a duo at each event.

That reconnection led to a band reunion in 2016-18 that spanned two explosive albums fulfilling every bit of the group’s earlier promise. With Divine Weeks’ declaration that their 2018 album We’re All We Have was their last, See returned to family life, only to become absorbed in first caretaking and then mourning his elderly mother. Five years passed before the encouragement of friends convinced See to take up guitar and pen once again.

The results were astonishing: his 2025 album Bow To No One is a triumph, a passionate and powerful statement of purpose and devotion to his partner, his community, and his country. Our recent chat with Bill See ranged far and wide, encompassing his chaotic upbringing, the early days of Divine Weeks, the doubts that creep into every artist’s mind, and the affirmation and recommitment to making music represented by Bow To No One.

THE DAILY VAULT: The albums that stay with me always seem to have a distinct vibe. Bow To No One has some of the elements of a protest record, but ultimately feels more like an effort to capture this really fraught moment in America. BILL SEE: I am very clearly left-leaning, but I went into this album feeling like direct critiques of Trump and MAGA were low-hanging fruit. There was a greater story I wanted to tell in this moment, of what it means to be an American right now. At the show I played a couple weeks ago, I said the thing that really, really angers me is when a voice of dissent is called out as somebody who doesn’t love his country.

BILL SEE: I am very clearly left-leaning, but I went into this album feeling like direct critiques of Trump and MAGA were low-hanging fruit. There was a greater story I wanted to tell in this moment, of what it means to be an American right now. At the show I played a couple weeks ago, I said the thing that really, really angers me is when a voice of dissent is called out as somebody who doesn’t love his country.

I love my country. I love my country. Although I am not proud of it in many instances.

I think one thing I do fairly well is read the room. I like to write about this country and the people who live here and are trying to live their best life. I think this is very serious stuff, but it doesn’t have to be all about this Trumpian nonsense. I think there’s a greater story to be told about coming to grips with who we are as a nation. That’s essentially what the record is about, all of us asking ourselves that question.

One of the lines that I like that you wrote in your review was about finding that maybe if our voices are all we have, let’s connect with that and let’s figure out what we truly care about and what is truly worth fighting for.

I’m glad that resonated. You’ve described the album as being like early Bob Dylan with The Clash backing him, but with acoustic guitars. First of all, great image. One of the amazing things about Bow To No One is that it feels like it has the bigness of a Divine Weeks album—that widescreen sound and depth of feeling—but transferred to a mostly acoustic setting.

For the first time in my life, at the very beginning of 2025, after years of playing on crap, I bought a nice acoustic guitar. I have a deep fondness for the sound of a warm acoustic guitar in the room that I’m in right now [See’s home studio space]. It’s very live. It’s a nice Martin guitar, and I held it in my arms and thought to myself, I want to write songs where this is the musical identity, but I want to retain the urgency of The Who, The Clash—that kind of clarity, that top line melody. I want to see if I can make this a folk-leaning record, but with the urgency that’s often missing, because sometimes it falls in a campfire-ness or becomes overly precious. (That’s fine, but I don’t do that.)

I like urgency, but I wanted the clarity of an acoustic guitar and I wanted to cast it in a rock setting, but with a folk identity. It was liberating because it forced me to get more precise with words and melody and the message itself. The message had to be more precise because the voice was exposed. I couldn’t hide behind the grandiosity of the overall production.

I was also thinking about the very first Alarm EP. The Alarm kind of got lost in the U2 cloud, but their very first EP was just acoustic guitars over pounding drums and it was like Bob Dylan and The Clash. That’s kind of where I was coming from. It’s too bad they didn’t they didn’t carry that forward; they kind of got sidetracked.

So I was thinking, what would it be like if I didn’t have amplifiers and it was all relying on my strength, passion, and urgency? With the acoustic, it’s about how much you lean into it. It forced me to dig down deeper, to be more precise and on point with my words. Every phrase needed to matter.

Another thing I liked that you said was something to the effect of, I wasn’t going to come back to make music just to screw around. There had to be a point to it. I liked that because it was true. I love frivolous pop like anyone, but I wasn’t going to come back to just fart out 10 songs that are just sort of floating along. There had to be a purpose.

And I did come back to music for a very specific purpose. I had a lot to say and I had some amends to make to my partner of many years. I lost myself in the last five years grieving my mom, having to caretake for her. I wasn’t attentive to our relationship like I should have been. And that was the basis for a couple of songs—you can probably identify them on the record—that were saying “Hey, I want to let you know, I’m back on the front lines. I still have fire in my eyes.” And there was not a better way to say it than with these songs. I wanted to let her know, let’s get out there. There’s marching still to be done. It’s not just believing, it’s doing. And that’s not to say that I think if we march against Trump today, it’s going to enact change. But there’s a cumulative effect that we can all contribute to. We all need to do what we can.

Part of it is probably just to feel a little better by getting back in the lane that is meaningful. Part of it is that we can’t let our joy be destroyed, because that’s one of the first things out of the fascist playbook, to take people’s joy and just pound them. And I love the idea of this surrealist form of protest, the absurdity of standing and smiling in the face of someone who hates you. I just think there’s something wonderfully powerful about that.

The Portland frog.

I love that! Fantastic. I went up to Portland with some friends in February right after the LA fires. It was one of the greatest weekends I’ve ever had. This was before the frogs and the protests. But I was embraced—there’s a lot of LA expats up there and I played a couple of shows up there. That trip was one of the things that really was the impetus for this groundswell of creativity. I came home and wrote six songs in six weeks after that.

I’d like to run a few quotes and ideas from Bow To No One by you and see what they spark. There’s a line in “The Heart Survives” that resonated with me—"Nobody’s really free until we’re all free.” It reminded me of the motto of one of my favorite fictional LA detectives, Harry Bosch, which is “Everybody counts or nobody counts.”

I’d like to run a few quotes and ideas from Bow To No One by you and see what they spark. There’s a line in “The Heart Survives” that resonated with me—"Nobody’s really free until we’re all free.” It reminded me of the motto of one of my favorite fictional LA detectives, Harry Bosch, which is “Everybody counts or nobody counts.”

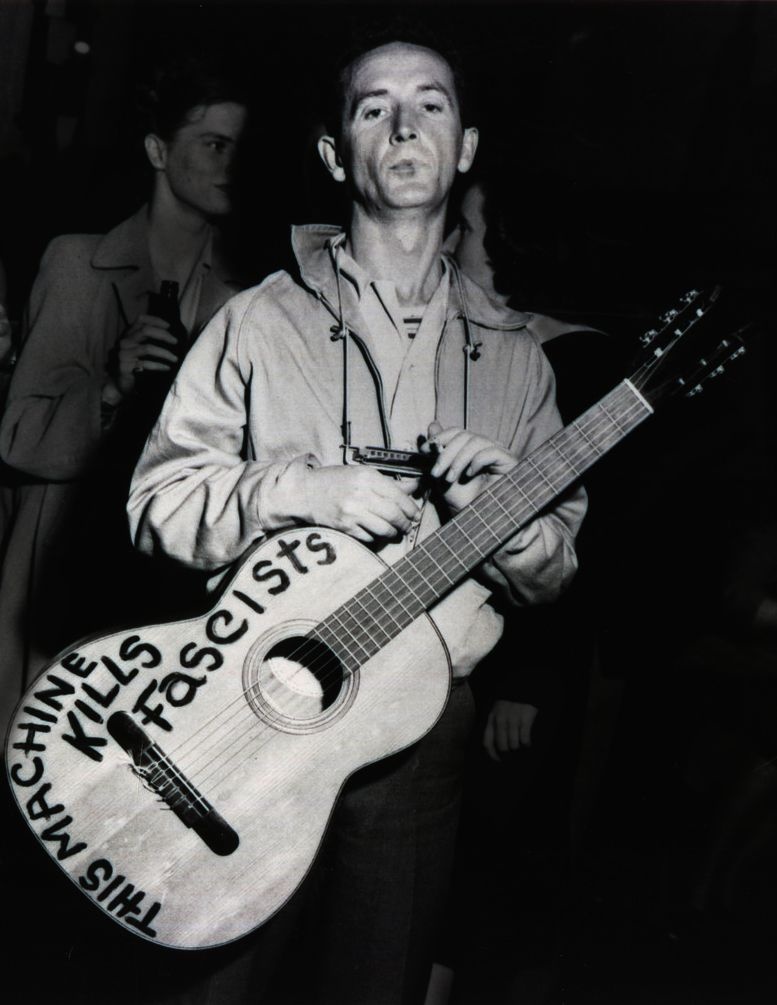

Yeah. The other line from the record that’s connected to that line is “Don’t you understand, we ain’t got a soul of our own? / We’re just part of a big soul that belongs to everyone.” That’s Tom Joad by way of Steinbeck, from The Grapes Of Wrath. And that connects with this whole idea of “No one’s really free until we’re all free.” My mom first told me that, and I think Springsteen also said it on The River tour when he was doing “This Land Is Your Land.” Woody Guthrie is the soul of this record.

If you had to trample over someone to get something, it probably wasn’t yours to be had—that’s the idea at the heart of that.

Another of the ideas that seems to drive a lot of your songwriting is of music as salvation. This time you actually wrote a song called “Rock And Roll Salvation.” Please talk about that idea and what it means to you.

First off, back in the day when I was an idiot living by indie rock rules, I probably wouldn’t have written a song like that; it would have been too obvious or whatever. But this whole record is me saying I’m not going to be embarrassed by anything. I’m going to be at my most raw, and if words don’t feel like they have to be said, then I’m not writing them down.

That song “Rock And Roll Salvation” is my debt of gratitude to Pete Townshend, Joe Strummer, Nick Cave, Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell and the rest—those are the sermons that meant something to me. That was my church, when the Catholic Church let me down. No offense to anyone, but the church left something hollow in me and it was rock’n’roll that truly was my salvation. It gave me a sense of purpose and it never left me. Maybe I left it for a while, but I felt like this was a song that needed to be sung and words that needed to be written—a deep, heartfelt thanks.

“To The Outsiders” channels the spirit of Woody Guthrie while borrowing a “hoo-hoo” or two from the Stones. You sing differently on it—it’s almost like a folk singer’s drawl and it works really well.

That guitar I mentioned, I put the capo on and gave it a drop D tuning, right in that wheelhouse of “Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall” or something like that. And I wasn’t trying to write a song, I was thinking “Do I feel like singing a Bob Dylan song right now?” I started playing and went, “Oh, that’s in there. But—I hear something.” You know? And it just kind of weaved its way into a song where I’m channeling the voice of Bob or Phil Ochs or Gordon Lightfoot or Jim Croce.

When I was a young kid I used to get earaches, and my mom would take me in her old VW Bug up the coast. We loved rain, but it didn’t rain enough in LA, so she would do the little windshield squirters, and we’d pretend it was raining, and she would put on Buffy St. Marie or Joni Mitchell or Simon and Garfunkel, old folk tunes. Those are my earliest memories.

Then when I had enough money to start going through the aisles of used record stores, I was looking for what got Bob Dylan interested in music, what he drew from. That led me back farther. I think it’s inevitable, if you pick up an acoustic guitar, that at some point you’re going to find Woody Guthrie.

But with Woody it’s not just the music, it’s the righteousness. I don’t think people realize this guy wasn’t just performing in auditoriums. He was riding the rails and hopping off and performing in encampments and at rallies out in the sticks. He’s such a mythic hero, he embodies the American dream to me in a way I don’t think people remember anymore. I guess that was why I was drawn to write a song called “To The Outsiders,” because for me he is our greatest outsider.

Maybe it started with Wall Street—"Greed is good”—or that whole idea of “morning again in America,” but when I was coming of age in the ’80s we were looking up at a president who really didn’t care about my dreams or my values, and it’s just gotten worse and worse, to where it’s considered wimpy to be woke. I mean, one of the lines in one of the songs is literally “I’ve been woke since the day I was born.”

As for Woody, everybody knows the first verse and chorus of “This Land Is You Land,” but they don’t know the difficult, unbelievably cool and heart-wrenching other verses. The one that really gets me is “In the squares of the city — In the shadow of the steeple / Near the relief office — I see my people / As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking / Is this land made for you and me?”

I think that’s the essence right there, going back to the idea that either we’re all part of this country or we’re not.

Around the time of the inauguration, I saw a lot of people reposting the famous photo of Woody Guthrie holding the guitar that says “This machine kills fascists”—it felt like it had another moment.

Around the time of the inauguration, I saw a lot of people reposting the famous photo of Woody Guthrie holding the guitar that says “This machine kills fascists”—it felt like it had another moment.

Yeah, but as wonderful as that photo is, there’s so many stories behind it. I wanted to go deeper; it’s not just name checking in that song. I don’t want to sound too self-congratulatory, but you write certain songs and you read them back and go “I have no idea how that happened.” I’m proud of “To The Outsiders.”

And I need to be able to say that, because I’m someone who makes a record and then dismisses it a month later. I still like Bow To No One—it means a lot to me, and I think it will always mean something to me because there was a force driving it. It happened when I came out of the wilderness after five years of telling myself I didn’t need music anymore.

The mind is a dangerous thing. If you listen to the wrong parts of your brain or the wrong voices, you can convince yourself of terrible things. I’m not saying I’m anything special, but I think I’m a good dad. I’m a great friend. And I write pretty good songs. You definitely want me on your side. And I like to combine these things.

And that’s what I do, but I’d forgotten it. Fortunately, I have a very special, small, inner circle group of friends. Most of them play music too. And you know, that song “Willie Says,” that’s a real person, Willie Aron. He said “Bill, you’ve got to get back to making music. I love you. I’ve seen what’s happening here. Respectfully, our days are numbered, but that doesn’t have to be a bad thing. It just means that it’s put up or shut up time. Get back to doing what you need to be doing, what you’re meant to do.” And I’ll always be grateful to him and the group of friends who came together at that moment and gave me a push. It’s no small thing that this record exists.

To back that up a step, what pulled you away from music?

A big piece of the answer to that is, grief.

My grandfather, who I called dad, when he passed when I was 20, I wasn’t prepared for it. Everyone deals with death differently, but I remember saying to myself “I will never be this unprepared for death again.” And of course, that’s fool’s gold—you’re never prepared.

My mother passed in 2023. And no matter what I did to brace myself, in hindsight I have to sort of ruefully laugh at myself. I thought I could be prepared for this? What was I thinking? In the time leading up to her death, I was her caregiver, and that took a lot out of me. It’s a very tough assignment. I wish I had done a better job, and I beat myself up over that.

In the process, to some extent, I failed my partner. As I mentioned before, she was still on the front lines with everything that was going on in the world, and I just couldn’t take it anymore, there was just too much news and I was grieving my mother and feeling sorry for myself.

As late as the [January 2025] LA fires, I was just sitting there, checked out emotionally, feeling kind of emptied out. And there was probably a lot more going on I didn’t even realize. Grieving a lot of time leads to taking stock of your own life. And I think I convinced myself that failure goes down a little easier if you just say you weren’t good enough—that it wasn’t about the breaks, it wasn’t about luck. It’s a self-flagellating, vicious circle to find yourself cycling in.

I feel like there’s something in creative peoples’ brains that does that, because I don’t think I’ve ever met one who hasn’t had a moment of serious existential self-doubt.

Sure. I know I’m not special in that sense, I know we all grapple with that. But when you find yourself isolating, it’s easier to tell yourself your dreams didn’t come true because you weren’t good enough. But fortunately, for me it’s not a happy ending, it’s a happy continuum. I did find a way to get out of there. And I have something tangible now that I’m proud of, and I’m grateful to those friends I mentioned, because that’s no small thing, and you don’t always listen. Sometimes you have great friends, but you just can’t hear them. Fortunately, I was able to hear them, and I was able to channel it.

The muse is a mercurial lover. She comes and she goes. And when she shows up, you’d better have your catcher’s glove on and be ready to receive.

People ask me “I’m starting a band. What should I do?” I’m no expert, but I can tell you one thing. Divine Weeks had about a nanosecond where we were kind of a thing on a small basis. But at that moment, we weren’t all rolling at the same speed. We were close, but we were not completely aligned. So when people ask me that, I say “The only thing I can really tell you is, when that infinitesimal little opening of that door happens and that little shaft of light comes through, you’ve got to all give each other that knowing glance and say, ‘This is it. This is our moment and we’re all going through this door together and we’re going to push that rock up the hill like our lives depend on it. And if we don’t make it, that’s fine.’”

I’m not saying that doing that would have led to superstardom for Divine Weeks. I’m just saying, that’s my one little kernel of insight from standing in front of that door. You have to all be aligned.

I remember John Lennon saying “Don’t fool yourself. The media made up a story for the Beatles for the masses. We were assholes. We were ruthless. We were careerists. We wanted it more than anybody and if anyone got in our way we flattened them.” Just remember that’s the truth and you need that. Fact is, with Divine Weeks, when that door was ajar for a moment, we were not all aligned to one singular dot on the horizon.

That’s a great set of stories and insights. And I’ve also gotta say: you guys were good enough, Bill. A hundred percent.

Thank you. It’s such a crazy thing, the rock’n’roll dream, it’s such a beautiful thing. I touch on it in my book. I think we’re all united by one thing: we all have dreams and for 98 percent of us they didn’t come true. And it’s reconciling that loss that truly binds us all somewhere down inside. When we’re young and stupid and wonderfully blind, we don’t understand the odds. Which is so great.

What’s the joke about the bee? He flies because he doesn’t know that physics doesn’t really support the idea of a bee flying. That’s the way I look at the rock’n’roll dream; if we knew the odds, if you really understood the unfathomable odds against you, well, you’d never pick up a guitar, right?

It’s too easy to know too much now. And I am very romantic about the launch of the dream because back then it was hard to find out the odds, in a wonderful way. It was the summer of 1987 and we were just young kids. We’d never even been out of the freaking house. Never traveled on our own. We hopped in a van because we didn’t know any better. We went down to Venice Beach and bought illegal calling cards. We scammed Guitar Center out of free gear with a lot of lies. Everything was seat-of-the-pants. We didn’t know it wasn’t supposed to work.

I had read in fanzines that you could look on the labels of singles and if you find a phone number, you call and ask “Can we open for you? Then when you come to LA, you open for us.” It was so provincial. We had that mentality, that youthful conviction, just screaming with belief against impossible odds. You don’t have any idea, you do it anyway, you just drive down the highway with a singular goal, everyone staring at the same dot on the horizon. What a great way to see the country and you get to play music, too. We were very lucky, I think.

Absolutely. That isn’t something everybody gets to do, and you lived to tell the tale. It seems like a big part of the story and one of the things that you talked about quite a bit in 33 Days was your friendship with Raj [Divine Weeks guitarist and co-founder Rajesh Makwana]. Please tell us a little about Raj and what that friendship has meant to you.

Absolutely. That isn’t something everybody gets to do, and you lived to tell the tale. It seems like a big part of the story and one of the things that you talked about quite a bit in 33 Days was your friendship with Raj [Divine Weeks guitarist and co-founder Rajesh Makwana]. Please tell us a little about Raj and what that friendship has meant to you.

(Photo: Divine Weeks - left to right, George Edmondson, Dave Smerdzinski, Bill See, Raj Makwana)

I just played a solo show last month and Raj was right next to me, up there helping out on guitar. That friendship endures. We were best friends when we started Divine Weeks, and he’s still my best friend. There was heartache along the way, but it’s an enduring friendship that’s about so much more than music.

When I met Raj, his family had just moved to LA from London—Shepherd’s Bush, the same neighborhood as Roger Daltrey. But he was attacked daily growing up there for being Indian. And when he came to the States, and it was the same thing here. All the way through high school, we were just two losers waiting for something to happen. He would look at his shoes when he talked and it touched me because it so reminded me of my earliest memories of my mom—they were both so painfully self-effacing. And I guess I always took on the role of protector with them both.

I didn’t understand his cultural struggle, because that was something he didn’t talk about too much. But the day we left on that tour, I remember he got in the van driver’s seat, and I was in the passenger seat, and he wasn’t saying anything. He was just looking straight ahead. And I’m like, “Raj, ready to go? Let’s do this.” And I looked up and there’s his mom, staring at us from the living room with this look on her face. And he was just frozen, still looking at her.

He didn’t say a thing about it. But when we got to San Francisco for the first stop, he pulled me aside and said “Bill, you don’t understand what it means to leave your family. You just don’t do it in our culture—we’re scared of separation. The culture is held together by family. You don’t really understand it.” And he’s right, because I grew up in pure chaos and all I wanted to do was get out of there.

So, the first half of that tour was Raj just trying to come to grips with the guilt of leaving for something he wanted as badly as I did. He loved what we were doing, what we built, but there was torment. I’m not saying the music was secondary, but just to get going, just to get it out of first gear emotionally, was such an undertaking. We were leaning on each other so much; I was trying to hold him up, he was trying to hold me up. It was a lot.

And then the guy who was the strongest of all of us, George [Edmondson], our bass player, by the time we got to Kansas City, three quarters of the way through the tour, he wanted to go home—not because he didn’t love the band, but because he got homesick, missed his girlfriend and was dealing with a huge choice coming that fall: go to grad school or stay with the band.

When we started the band, George would say, “I’ll be like Sting. I’ll keep working toward becoming a professor, and we’ll go on tour in the summers.” But we already had a big tour booked for that fall and by the time we got to Kansas City, I was waxing on about the whole DIY slow ground war we were fighting like our heroes The Minutemen and Hüsker Dü. George just kept saying he needed some tangible evidence that we were gonna make it big, so he could justify touring that Fall and cut the cord on grad school.

If it wasn’t for Dave [Smerdzinski], our drummer, who was the only one of us who’d lived on his own before this tour, we probably would’ve ended up in the fetal position on the side of the road in Kansas. We were just trying to grow up.

But this wasn’t just another “jump in the van” indie rock tour. The watershed moment on that tour for me will always be that night in Edmonton when Raj was attacked racially. It really shook us to the core. I’d never seen anything like it. We weren’t physically beat up, but we were verbally, aggressively taunted and threatened by a bar full of rednecks. I’ll never forget, when it was all over, Raj’s whole face turning ashen with shame as he looked around at us watching him.

It was such a profound moment in all our lives, to have this happen just when it felt like the band was clicking, starting to come to grips with things. We almost turned around and went home right then, and for a couple of days we weren’t sure if we were going to be able to make it.

Two nights after that, we played a show in Regina—I talk about this in the book—and as we started playing, we just all gravitated toward each other. We were just playing to each other, in a circle, and it’s like the audience just happened to be there. We just needed to play for ourselves. No one said anything, it was like a little rehearsal, as if we were taking it all back to the beginning again, connecting to why we started playing music together in the first place so we could figure out if it still mattered, or if we were doing it for the right reasons. Everything really clicked then. We found our purpose, and it was really fueled by this moment that we were able to overcome.

I don’t know. I just don’t think a lot of bands had a tour like that.

I love Raj. He is the most important friend I’ve ever had. We’ve made music, we’ve cried together, we’ve fallen apart together, we’ve risen together. We’ve come to an understanding how important it is to show our kids that we still are dreamers and that we aren’t just sitting around the coffee table as they come and go in their lives. We owe it to ourselves and them to shine some light and stay busy coming up with new dreams. That was something that we bonded on as adults, and that’s still going on. He checks in with me all the time, and I check in with him. It’s a blessing to have him in my life.

People join bands for all kinds of reasons, but one of the common ones you hear is that they’re trying to create an alternate family or a new family because their own is problematic for one reason or another.

People join bands for all kinds of reasons, but one of the common ones you hear is that they’re trying to create an alternate family or a new family because their own is problematic for one reason or another.

(Photo: Divine Weeks on opening night of the 1987 tour chronicled in 33 Days)

That’s true. When Divine Weeks happened, I was trying to escape. I was that classic story: “I need to get out of here, whatever it takes.” I’m going to get in that van, go as far as I can and reinvent myself, become someone who doesn’t have this past. My mom was a very difficult mom to love. She was mentally ill and on drugs. I absolutely needed to find an alternate family or I would’ve gone mad. But it’s also true that my mom is the reason I sing. She’s the reason I write. She’s the reason I am an artist, if I can say that out loud. So, there was a lot there. But it took a lot for me to realize all this. When you’re a kid, you can assimilate and adapt to anything, right?

Raj, he joined the band because he heard those voices inside, and just like me, music was his salvation. At the same time, he was trying to reconcile that urge to get away, with the expectations of his culture. At some point he was going to have an arranged marriage and he was going to have to leave music behind. In the end, he revolted against that and married for love. But that was a hard-fought battle and Divine Weeks was ultimately one of the casualties—and our friendship, too, for a time.

I think 33 Days would have worked even if it was about a band of comedians or mountain climbers, because it’s really just about reconciling that first dream. We’re all united by desperately wanting that first dream, and by having to reconcile that thing we wanted so badly that didn’t quite happen and figure out a way to move forward. I think that’s a galvanizing force for a lot of people.

There’s one detail in the book that jumped out for me, maybe because I had three different stepfathers growing up. You wrote about how your stepfather deserted you and your mother—and yet you kept his last name, See. Why?

That’s a great question. Maybe I should’ve taken my mom’s maiden name, Yates. That would’ve been such a literary name: William Yates. George wanted me to call myself by some sort of punk rock nom de plume: Will See. In the end I guess it just felt like it was too much of a hassle to change my name. It’s not a very rock’n’roll thing to say, but I guess it was pure logistics.

How did your mother feel about 33 Days? The book feels like it’s very honest about her strengths and shortcomings as a parent.

A friend of mine said “You wait till your mom’s dead for this book.” But right before I published, I had a conversation with my mom and God love her, she said “Don’t you dare pull punches. You tell your story.”

On the promotional tour for 33 Days, you and Raj played duo versions of some Divine Weeks songs at each event. And I’ve read that that’s what brought about the reunion of the band in the twenty-teens. How did that come together and what did it feel like?

On the promotional tour for 33 Days, you and Raj played duo versions of some Divine Weeks songs at each event. And I’ve read that that’s what brought about the reunion of the band in the twenty-teens. How did that come together and what did it feel like?

When I was almost finished with the book, I felt like something was missing. So, I asked Raj if he could give me more details about growing up in England and what he went through so I could help the reader understand why he was so conflicted. And he gave me all sorts of great background and some really heart-wrenching details about the abuse he took that I had no idea about. I think it made the book more multi-dimensional to have his voice, to have him provide those details as to why there was so much torment for him during that tour. Without it, I think the reader could have easily mistaken his reluctance to embrace this grand adventure for him just being a goody two-shoes or something, you know?

The first show of the book tour was up in Seattle, and LA to Seattle, that’s a good long drive. At that point, it wasn’t that we were estranged, but we had never really talked about the end of Divine Weeks. As it is with most bands, there’s always some heartache or a power struggle or whatever that breaks bands up. For us, it was, in large part, a byproduct of Raj rebelling against his culture, rejecting an arranged marriage—and by extension the band—so that he could be with the person he ended up marrying. The irony was, the courage he found making music with us and going out on tour and all the rest was the watershed leading to him turning his back on us. So, long story short, there was a parting of ways, and we went on without him for a time.

Anyway, it was on this long drive from LA to Seattle that we talked through that whole thing and got it all straight in that kind of classic case of two men on a road trip with a lot of coffee. We’d go “Well, we could stop here.” “Nah, let’s keep going because we’re getting somewhere now." That conversation was like a movie in itself, just us getting to the bottom of everything so we could have a second-half-of-life adult relationship, so we could take this to the end. That was basically the goal without either of us saying it out loud.

I think one of the things we came to grips with was, how are we going to be as fathers and what kind of dreams can still exist in the second half of our lives? The impetus for writing the book was a moment I think we all have where we wake up in the middle of our life and look around and go, “What do we have here? How did we get here?” I’m so glad I let Raj into the process of writing the book, and it became yet another facet of our friendship.

The album I’ve been listening to the most in the last two weeks is the last Divine Weeks album, We’re All We Have. It feels like you were all determined to leave nothing on the field. Was that part of the rationale behind presenting it as the group’s final album? Was that intended to get that “last chance” energy flowing? That’s certainly the way it feels now. I don’t think it was that planned out, though I knew that was going to be it. I don’t think we needed self-motivation like that, not in 2018, in the middle of the first Trump term.

That’s certainly the way it feels now. I don’t think it was that planned out, though I knew that was going to be it. I don’t think we needed self-motivation like that, not in 2018, in the middle of the first Trump term.

That album is another example of trying to come to grips with who we are as a people; Bow To No One is something of a companion piece to We’re All We Have, unintentionally. I would say We’re All We Have is a little bit more incendiary in some spots, a little bit more visceral and direct. And at the time, who knew that there was going to be a second term of this maniac? At that time we were thinking “Wow, this crazy thing happened, let’s just try to get through it.” Who knew that he was going to come around again? I thought we could all agree fascism has no place here. I thought we all remembered we already fought and won a war over that, but I guess I was wrong.

To get back to your question, yes, we wanted to leave it on the field. And I think we did. There is closure now for Divine Weeks. And I’m happy that record speaks to something that resonates then and now. I hope we’re all searching for answers as Americans. We’re All We Have started a conversation for me, and I think Bow To No One is a deeper commitment to getting answers.

It’s hard for me to write a simple love song, I guess. [laughter]

There have been an awful lot of those written already, so…

Don’t get me wrong, I love a great love song, and God love the people who can do it, the craftsmen—here’s to you. I tend to write in blocks, around a particular set of ideas or experiences. If you want to know who I am and where I’ve been, all the answers are in the books I’ve written and the shows I’ve played and the albums I’ve made. There are no mysteries. My life is in the art itself.

I’m in the throes of writing a new record now and I’m already moving forward and—no promises yet—but I picked up the electric guitar, which almost feels like a novelty at this point compared to the last record. I’m coming to grips with what it means to be in the second half of my life, and grieving, and asking myself, what’s left?

Maybe all there is left is artistic transcendence. Spoiler alert! [laughter]

People pursue art for different reasons. Do you think the pull is stronger when it’s more of a form of therapy or versus when it’s about ambition and a drive to be seen and heard? Or are those two sides of the same coin?

People pursue art for different reasons. Do you think the pull is stronger when it’s more of a form of therapy or versus when it’s about ambition and a drive to be seen and heard? Or are those two sides of the same coin?

(Photo: Raj & Bill, 2018)

It’s been said that there’s a very, very fine line between drama and melodrama. I think the greatest art encroaches on that line. I also think the best music, or at least the music I turn to the most, cannot exist as background music. The music that matters to me climbs through the speakers and demands my full attention. And after it fades off, it remains with me. It haunts me, relentlessly.

Again, we’re back to what moved me to make a new album. I’m only going to do it if it’s something that serves some sort of therapeutic purpose for me. At the same time, I do want to connect with people, and music is my way of making that connection. I don’t want to just write about a nervous breakdown; I want to share how I was able to break through. Maybe it’s not always a pretty story, but I do want to write something that’s relatable.

I think as you do this longer, hopefully you start understanding what you do well. I feel like there’s just a couple things that I’m pretty good at. I don’t need to become great at a hundred different things. I just want to keep getting better at the few things I’ve got some traction and some mileage with. I don’t need big numbers. I don’t need a lot of followers. I don’t need a lot of adulation. I’m just here surviving best I can to my last days, and I want to do it with honor.

And, I want to do it with songs that the people in my life who know me can go, “That’s the best thing he’s ever done.” That means everything to me. People who’ve been on the road with me, cried with me, lost other people with me, I would probably insult them to say they’re my audience; they’re just friends, but those are the people who mean everything to me. To have some of those people who’ve been on that journey with me telling me that Bow To No One really touched them and that it served a purpose, helped them start asking themselves questions about where they are or who they are in this moment in 2025—that’s everything.

It makes me feel a little bit better about the fact that I had turned my back on music for a while. I’m very sorry that happened—five years of wandering the wilderness. But it was really nice to hear somebody say “Bill, where was the music? Come on, don’t let that happen again.” It’s special to have friends like that.

Maybe that time away is what you needed to get to Bow To No One. You don’t always know what the moment you’re experiencing is feeding into your creative engine, but the creative engine is always there.

We talked earlier about the mercurial muse. Neil Young was asked “Why did you do this record? The fans, they can’t follow you. They don’t know which way you’re going.” And he said “I only listen to the muse. That’s where I go. That’s who I serve.” I remember hearing that early on and that is the guideline. If there is some sort of higher power for an artist, like I said, just keep those hands out and be ready to receive. It’s gonna flow through you and you’d better be ready, because it’s gonna come and then it’s gonna go.

With Bow To No One, it was crazy. After that weekend in Portland, I got home and songs just started coming like never before. My partner Cindy said “It’s funny, you go in that room, and you come out and there’s a song. And you do it again and there’s another song. I’ve never seen you like that.” I could’ve kept writing and I did think to myself, “Why am I stopping?” Because writing is the most fun part. But I wanted to get the record out because it felt so fresh and timely and I needed it out there.

It feels almost rude, but now I have to ask: when’s the next album coming out?

It feels almost rude, but now I have to ask: when’s the next album coming out?

I’m glad you asked. The fact that I am in the throes of a new record at all—which I am—is the best news of all. Bow To No One was not a one-off. I've got eight new songs recorded. I’d say I’m leaning a little harder on the electric guitar for this new batch of tunes.

But you know, it’s not about just writing enough songs for a record. It has to feel like a record, and I’m still coming to grips with what I’m writing about. I’m still coming to grips with my mom’s passing. And I’ve been trying to recover from a leg injury the past couple months which has slowed me down and played on my mind—made me start pondering mortality and taking stock of things. We’ll see where the muse takes me. Now that I’ve accepted I’m in the second half of the race, there’s a little more sense of urgency and more of a focus on personal transcendence.

It seems like every time I do an interview where we dig deep into what makes people want to do creative work, the conversation lands on transcendence. I feel like that’s what we’re all chasing, and the conversation always seems to arrive right here.

I think it’s just where we’re headed. It’s the inevitable destination. There’s a stripping away of artifice and facade. That’s what I’m trying to do now; I’m stripping everything away so that I can get to the bare essence. I don’t know if I’m going to be standing at the pearly gates or purgatory or wherever, but I want to make sure that when I get there, I’ve got what I need. It won’t be much, but it’ll be essential.

#