Features

Gregory Spawton of Big Big Train: The Daily Vault Interview (2024)

by Jason Warburg

The backstory of Big Big Train is long and eventful enough to fill a large book—which in fact it has. Rather than recap decades of activity, though, let’s skip to the essentials. The British progressive rock collective was co-founded by songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Gregory Spawton and, after traversing various hills and valleys, hit its stride in 2009 with the arrival of Nick D’Virgilio (drums/vocals, ex-Spock’s Beard) and David Longdon (lead vocals and many instruments). More recently, the band experienced a series of calamities.

The backstory of Big Big Train is long and eventful enough to fill a large book—which in fact it has. Rather than recap decades of activity, though, let’s skip to the essentials. The British progressive rock collective was co-founded by songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Gregory Spawton and, after traversing various hills and valleys, hit its stride in 2009 with the arrival of Nick D’Virgilio (drums/vocals, ex-Spock’s Beard) and David Longdon (lead vocals and many instruments). More recently, the band experienced a series of calamities.

First, in 2020 the combination of an increased focus on touring and the COVID pandemic led three of the group’s seven members to reassess priorities and make their exit. A year later, just as the remaining quartet (Spawton, Longdon, D’Virgilio and guitarist-keyboardist-vocalist Rikard Sjöblom) had assembled a new lineup and completed work on two new albums, tragedy struck. In November 2021, David Longdon was critically injured in an accident and passed away at the age of 56. Spawton had barely had time to consider the future of the band—which resolved as a group to carry on, as Longdon had wished—when his beloved stepfather received a diagnosis of terminal illness.

These losses factor substantially into the band’s new album The Likes Of Us (March 1), the group’s first for Sony’s Inside Out label after a quarter century as an independent band, and the first to feature new frontman Alberto Bravin, as well as new keyboardist/vocalist Oskar Holldorff. (Rounding out the current lineup are continuing guitarist Dave Foster and violinist/vocalist Clare Lindley.) It’s a transitional album for a group seeking to both reestablish its identity with its core group of fans, known as the Passengers, and connect with a wider audience. Where many of the group’s earlier songs brought tales from history to life, The Likes Of Us is for the most part a deeply personal album about how our connections with family and friends can sustain us in a time of loss. For all that, it’s a fundamentally uplifting listen, 65 minutes of stirring progressive rock brimming with superb musicianship and fueled by a message of hope and resolve. Life throws a lot at us, this album says, but with the support of our family and friends (and band), we can and will carry on.

Big Big Train will play its first ever shows in America in early March, on the cusp of the new album’s release. In anticipation, we recently enjoyed a lengthy chat with Gregory Spawton about The Likes Of Us, delving into topics including the importance of album sequencing, how to accidentally write a 17-minute song, the accumulated wisdom of Spinal Tap, and that magic moment when a band and audience become one. Enough backstory, then; it’s time we got our skates on.

The Daily Vault: The last time we spoke on the record was in 2016, between Folklore and Grimspound. Back then, I asked you to imagine it was five years in the future and talk about what you hoped Big Big Train might have achieved over that period of time. You mentioned four goals: to continue to make good and moving music; to play some shows that will stick in people's memories in a positive way; to make at least three new studio albums; and to gig a bit more widely. By my count, the band achieved every one. And yet, the last few years have been very difficult ones for you and the band with the pandemic, the lineup changes and David's very sudden passing. What has helped to keep you steady and moving forward through everything that's happened?

Gregory Spawton: The most important elements have been friendship and family. Without those things, I probably would have been sunk. That sounds a bit dramatic, and I try to be a cheerful person, but we've had some extraordinarily difficult times in Big Big Train. First, around the time COVID happened, a number of the band members began to think “Actually, I'm not sure I want to be spending my life in the confines of a tour bus”—which was the direction the band was headed, and has since come to pass. We did 17 shows last year and that was all on the tour bus. And you are in close confines with people, and several band members just basically said “I'm not gonna do that.” So the band began to feel like it was falling apart around our ears and what propped me up then was the fact that the four of us, me, Rikard, NDV [Nick D’Virgilio] and David, stuck together as a close-knit group.

The COVID era was terrible for everybody, but the impact on musicians was particularly acute. And then we lost David, and of course that was the most shocking and unexpected loss that you can imagine. It was one of those things where you wake up in the morning and your life has completely changed from when you went to bed. Literally. That was an extraordinary thing to go through. My life's been a bit weird because I didn't become a professional musician until age 54 or so. It was a hobby, then a serious hobby, and then it began to become a career. And then suddenly I was facing the loss of all that and the loss of an incredibly dear friend. David and I were like brothers in many respects.

It didn’t feel like it could get much worse and then just a few months later, my dear stepdad, who's the only man who really has been a father to me, fell terminally ill and went through almost a year of misery. There’s an awful lot that has gone on that’s been very difficult to bear and my dearest, dearest wife, my family and some friends—particularly some old friends that sort of came out of the woodwork—were there to prop me up and support me. It was those kind of things that kept me going, and of course the band members, new and old.

But that was it—human companionship, having someone to talk to. Before these things happened, I would say I was quite happy in my own company and didn't always feel like I needed other people that much. And then when the chips are down you realize that you do. It was those friendships and companionships and family life that really have kept me going.

That comes through on the album, which represents something of a turning point for the band, both because it introduces the new lineup as a songwriting and recording unit, and because the music itself continues to evolve. The songs on the album tend to be grounded more in the personal than the historical, focusing on friendship and personal connections. How much do you feel the content and tenor of The Likes Of Us grew out of the circumstances that you and the band had just been through?

Substantially so. It would have felt crass to do anything other than write about our own personal experiences this time. I guess there were two things we could have done. One is just to go “Right. Let's go into a fantasy world” and find a lot of stories to tell in order to absent ourselves from what happened.

Another is to deal with it head on, and we chose the latter route. As a writer, you know that sometimes you just have to go with the flow, you almost don't get the choice. I haven't written many personal songs in recent years, but because of what's happened, I just didn't feel it would be honest to do anything other than to write about our own personal lives and recent experiences, and how we've responded to those and how they have helped to form the band as it stands today. So that's what we did.

There is one story song on there [“Miramare”]—I didn't want to abandon that and I'm sure we'll go back to that in the future. But you're absolutely right, it was an album that had to be personal, really—I don’t think it could have been any other way.

I know that feeling well of trying to steer the writing one way and having my life and what's going on with my emotions steer me in a different direction, because that's what I needed to be writing about.

Exactly. It almost takes hold of you. Sometimes I know what I want to write about, but I don't know the angle that I want to come at it from, and then suddenly something will just hit you and you'll figure it out. You're not sitting there thinking about it, but it will just suddenly appear in your mind and you say “Oh, I'll take it that way.” We just thought, okay, the stories we need to tell on this album are about our own lives rather than about other people's lives, for the most part.

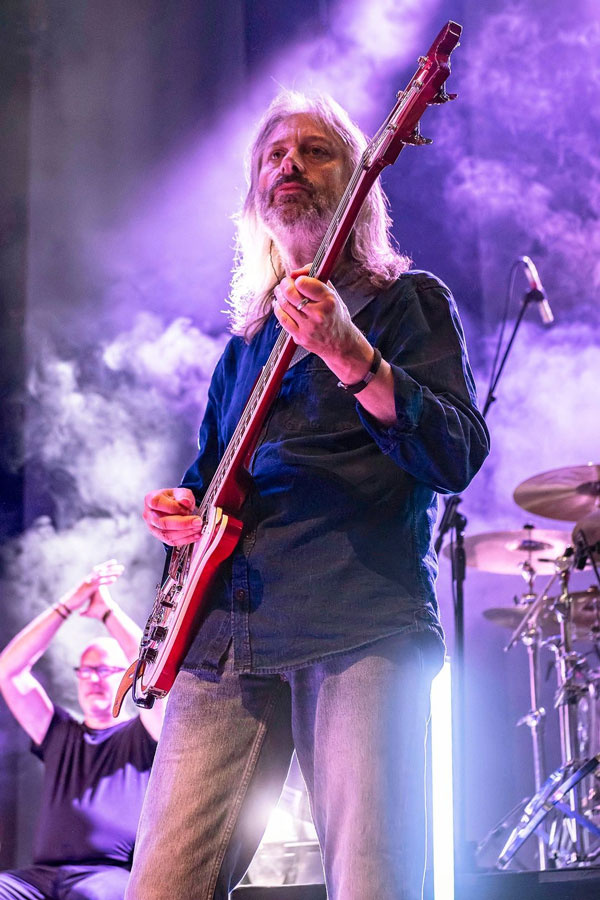

Oskar Holldorff, Dave Foster, Clare Lindley, Alberto Bravin, Gregory Spawton, Nick D'Virgilio, Rikard Sjoblom

[Photo credits: concert photo (above) by Michael Heller; band photo by Massimo Goima; portrait photo (below) by Sophocles Alexiou]

Another theme that's apparent in several places on The Likes Of Us is “carpe diem.” Seize the moment. Don't wait, because you never know how much time you may have.

Yeah, absolutely. There’s one that's really on the nose on that called “Skates On.” I don't know if that phrase means anything in the States, but in England it means “Come on, get on with it, get your skates on and stop procrastinating.” I just had the phrase “Get your skates on,” and then I thought, actually, just reduce it to the bare minimum words, and it became almost a rallying cry.

That song is a bit Beach Boys-y, a bit XTC, it's sort of a light-and-shade moment on the album. I think if we'd have hit everybody with 10-minute epics only, it would have been a bit too much. But there's a serious bit in the middle eight of the song about going out on your shield and really trying to seize life by the short-and-curlies. And sometimes that means watching telly and reading a book; you also have to be able to just sit back and take some time out and go for a walk or whatever. It's not all about being madly productive; I think we make that mistake sometimes. But it's about trying to achieve things while you can, you know, making hay and all that sort of stuff.

I have a series of questions about the individual tracks on the album, but first, a comment: as you’ve just noted, album sequencing matters a lot.

Couldn’t agree more. There’s a real art to getting an album sequenced correctly. I remember the old days, when an artist had only written three decent songs and they need 10 on the album, they would put a couple of the good ones at the top and the other good one at the end. I think one of the beauties of progressive rock, particularly albums like Wish You Were Here or Dark Side Of The Moon or Selling England By The Pound, is that it really feels like the artist has thought things through.

It’s a cliché, but an album, it’s a journey. You put the needle on the record or put the CD in and for me, the mark of a good album is that you feel you have to get to the end of that journey. Pacing it and then selecting the songs in the right order is really, really important.

On the new album, the opening track “Light Left In The Day” serves as somewhat of an overture, previewing both lyrical and musical ideas that appear subsequently, and I was interested in how that's almost an inversion of the way “The Permanent Way” functioned to sum up the English Electric albums.

I'm glad you mentioned “The Permanent Way,” because that's the other time we’ve tried this. I wrote “The Permanent Way” and it was a really difficult thing to deliver because we had a lot of music and I just wanted to try and find a way of putting those themes together in a piece. Alberto is very much on my wavelength with regard to making albums. We had the album pretty much in the bag in terms of writing and he said “We need an overture.” So I said, “Great; go and write it!” [laughter] Because I know how difficult it is to do that. So, bless him, he took the challenge on and thought very carefully about the crucial motifs and themes on the album and brought them together.

He sent me a work in progress and I said, “Yeah, you're really on to something here, you managed to find a way of combining many of the crucial themes.” I think one of the nice things about that is the sort of guessing game, the musicological aspects of it. Because there's so much in there, people will not pick up on what themes or motifs we're redeploying or establishing until maybe the 10th or 15th listen. That's happened to me—I remember, it was Wind And Wuthering by Genesis—I read somewhere there was a theme on “Eleventh Earl Of Mar” that appears in a later song and I didn't even know and I’ve listened to that album a hundred times! I went away and listened again and thought “Oh, that's really clever. They planted that so deep that I didn't spot it at all.”

I'm hoping that's what will happen with this album. What we ended up doing [with this track] was we had the complete piece, but I had a little section of music called “Tail Enders,” with a cricket theme, which was going to be a hidden track at the end of the album. And I thought, actually, let's see if we can combine these two ideas and make them into a single piece. After a crafty key change—which was easy because the “Tail Enders” thing was just acoustic guitar and vocals—we managed to find a way of segueing the two. The brass band kind of picks up from the end of this acoustic guitar piece and I think it's a lovely little thing. It's actually very hard to play; it sounds easier than it is, so I think when we're playing live, the keyboard player will be up there flexing their muscles ahead of playing that, especially if we play it first at the top of the show.

I'm very proud of it. I think Alby did a great job in delivering something that makes you feel like you're heading off on that journey.

It also felt like that track gives an opportunity for everyone in the ensemble to shine; it almost felt like a proof of concept for the new lineup.

Yeah, I agree, that's pretty much how it comes over to me.

“Oblivion” is a Dave Foster-NDV co-write that feels like one of the heaviest songs that Big Big Train has recorded to date. You could sense a little bit of a stir on social media when it was the first single to be released by the new lineup. But in the context of the full album, it feels to me less like a musical departure than a natural complement to some of the gentler passages of music on the album, including the bridge to the song, which is very dreamy and airy.

That bridge, I think, takes the song up a level. It's actually a surprisingly complicated song, because it sounds riffy and heavy, but there's some time signature stuff going on there that's quite tricky; sometimes you find yourself counting it when you're playing it. And yeah, Dave delivered a kind of riff-driven thing that we haven't done much of recently. I’ve been a little frustrated in recent years that we've got sort of a reputation as a folky, proggy band rather than a rock band. I love rock music and I'm very pleased to think we'll be doing this more in the future. We're never gonna be a heavy metal band, but I think it's good that occasionally you can get the guitars out and get some heads banging a bit.

It's got a nice sense of energy for me, this one. We come out pretty heavy at the top of the song, but then you've got that bit in the middle where it does get very dreamy and floaty and some lovely textures there. It's good fun. We've played this one live already and it's been quite well-received.

Have you gotten the sense that it took some listeners by surprise?

It does seem that having it be the first single had some people thinking “Oh! That’s a departure…” But as you say, in the context of the whole album, I think it feels more right. As you know, we did a song called “Make Some Noise” many years ago. It’s almost a bit of a Queen pastiche, that one, and it kind of horrified a good half of our fan base, while the other half sort of saw the musical gag in it. But at that point in time we were a little bit apologetic about it because it felt like “Serious prog bands shouldn't do anything light-hearted.” But “Oblivion” is different, more of a serious piece of music with serious lyrical content, but certainly a bit more up-tempo and rocking—not a bad thing for me.

Let the record show that I was in the half that enjoyed “Make Some Noise.”

[laughter] Okay, cool. I remember when we played the first live shows back in 2015, we thought “Everyone's going to expect us to encore with it.” And we just thought “Let’s do the exact opposite and play it right at the top of the gig” and then people can just get on and enjoy. And then two or three songs later we were playing 23 minutes of “The Underfall Yard,” so people thought “Okay, they can cover both bases here. They're not just gonna be the easy-going pop-rock thing” that that song seemed to suggest.

It's always been fascinating to me that, in my experience, progressive rock fans often don't like it when the bands they follow actually do progress.

Oh, yeah! You can't win. You get criticised for releasing an album that sounds a bit like one you've done before, and then you get criticised for trying to be different. So you think, “Okay, so our goal is just, be good.” We'll just try to be good—write the music that speaks to us, and it's gonna broadly be based in progressive rock, but we reserve the right to go off on tangents from time to time, as I’m sure we will do going forward.

Next up, “Beneath The Masts” is an extended epic of over 17 minutes that celebrates a personal connection and the experience of loss when it ends. The language of the lyric is both specific and somewhat ambiguous, which leaves room for the listener to add their own context. I was struck by what an astute approach this is because the loss of a person you care about is something that just about everyone will experience in time. The specifics may be individual, but the experience is universal.

Yes, exactly. And you know, once you release a song, it's no longer your own. People sometimes get the wrong end of the stick with songs. Occasionally they get them so spectacularly wrong that you feel the need to correct them. But it’s no longer my song. People will read into it or get from it what they will. Because of interviews like this, people will know what I'm trying to speak about with “Beneath The Masts,” but it'll relate to their own experiences and hopefully it will speak to them. As you say, unfortunately it’s a universal experience, we're all going to have to process these things from time to time.

I especially enjoyed that this piece, that has a number of really dynamic instrumental passages and a real sense of scale, also uses a central image that for me at least, called back to “Winchester from St. Giles’ Hill”: the narrator climbs a hill to see the view. I know this is a different, specific hill, but I found that parallel striking.

Yes, that's a good point. That actually hadn't occurred to me, but there’s definitely a parallel there. The hill in this song was at the back of our garden when I was growing up. We lived in a strange place called Moss Drive and it used to be a quarry. If you just drove up the road, you'd think, well, this is a fairly normal kind of semi-detached house street. But when you went to the back gardens of the houses, suddenly you'd find yourself walking a hundred yards and you go right up a steep hill. And from the top of that hill, you could see 20 or 30 miles of West Midlands.

As a kid I loved it up there. I spent my lot of my childhood free-ranging it up the back of this hill, because you were away from the house. You're away from your mum and your dad and all those things. You would experience things there as you transferred towards adulthood—your first kiss, that sort of thing. But it all took place on that hill at the back of the house and these television transmitter masts were there, two of them, and they seemed to be a backdrop to my life, really.

I mentioned in the song where you could see, as dusk fell, people coming home in their cars and it was quite evocative. It was a place where the adults didn’t really go because it was a bit of wilderness, a bit of edgeland at the back of residential area. It was a place that we could call our own as children and it was our haunt, really. The masts appear in the title of the song because my childhood was there, with those things in my permanent view.

As my stepfather became ill, I found myself having to return home more and more, and he ended up in a hospice underneath this mast. So that was where all of these kind of thoughts started to float around and I was trying to find a way of seeing my way through this song about loss and grieving and all those things.

But not just grieving for my stepfather—also accepting the loss of my Midland roots, almost. I’ve still got friends up there, but they're mostly behind me. My mum's moved to the South Coast after my stepfather passed away. And so my heart's still there, but it's unlikely I'll go back, apart from maybe on tour. So it just felt like I was losing touch with where I grew up and where my identity was formed.

That feels like it calls for an epic.

Yeah—it didn't feel like an epic when I was writing it. NDV a wrote section of music in there, but I wrote everything wrapped around that, and I didn’t know what I was dealing with, really. I was away for a few weeks in Rome when I was writing it and I had bought this cheap 12-string guitar at a store and I didn't have Pro Tools or anything, I just had on my phone. So I was writing away and one day I just sat down and tried to play the whole thing through. I genuinely, hand on heart, had no comprehension of how long it was. I knew it was more than three minutes, but I thought, “Is it seven or eight minutes?” And I picked up the phone at the end and the voice memo was 17 minutes long. So I thought “Oh! Okay, so it’s one of those.” [laughter]

I hadn't written lyrics at that stage. You’ve got the melodies in your mind, but you're ad-libbing vocal lines. And then you'll find sometimes those words have the mouth feel that you need, so they'll end up going into the narrative of the song. But I just had this long piece. I came back from Rome with it and nipped into Rob’s studio locally to try and get a demo together for the rest of the band. Nine times out of 10 now, I know when something works and I thought, “Okay, I think this works.”

Importantly for me, there was a kind of happy ending. I didn't want the song to be just completely miserable. I've got a friend, an astrophysicist, a chap called Stuart Clark. And I said, “I think I know the answer, but what happens to our atoms when we die, what happens when we pass away?” He explained the process and it happened that my stepfather died in spring, so I had that dichotomy of him passing away along with new life emerging, and that felt to me to provide the song with the ending that it needed, which wasn't just all doom and gloom.

You have to go through the grieving process as I have done with David and with my stepfather. But, beyond that, sometime, somehow you have to find a way of picking yourself up and trying to carry on with life, because that's the only way forward.

It strikes me that this makes “Skates On” the perfect song to follow.

Yeah. Coming back to the conversation about how you construct the narrative of the album as a whole, not only did it musically feel right, in that you needed a breathing space before we got sort of heavy again, it felt like absolutely the correct lyrical message to deliver after “Beneath The Masts.” It's “Get on with your life.” No matter how difficult it gets, do your best to keep going and keep moving forward. That's it.

“Miramare” is the second longer track on the album at just over 10 minutes. It's based on a story that's part of the lore of the city of Trieste, where the album was recorded. Could you tell us about the story behind the song?

As I said earlier, we didn't want to completely abandon the storytelling element of the band. Alberto had written this piece of music specifically for the album and had improvised some vocal lines, so there were a few words floating around in there, and he suggested a story song, specifically the story of Maximilian and Carlotta. My historical interests lie primarily in ancient Rome, ancient Greece, Anglo-Saxon histories and much further back in time, so I didn't know anything about the Habsburgs at all, but I expect not many people do.

It was a steep learning curve for me, and I think I ended up reading five books on the subject. I was trying to find the way through this, the hook, the angle. Maximilian was a kind of a prince who was looking for a role, as he wasn't going to become one of the leading rulers in Europe. He was given the job of going to become the Emperor of Mexico as the European powers tried to hold on to their imperial possessions. His wife Carlotta was a Belgian princess, so it was very wealthy people trying to impose European norms on a completely different culture and it was a fool's errand. It was a crazy thing to try to do, and in the end, it would not hold. Carlotta returned home, and Maximilian ended up in front of a firing squad.

Immediately I was thinking it was quite a serious story, but it's got some interesting things about where we find ourselves in the world, now and in recent centuries. Poor Carlotta ended up going mad. She literally lost her mind and became, I think, probably a paranoid schizophrenic, looking at the symptoms that she was experiencing. So it was almost like a Macbeth kind of story, and that attracted me, that there was quite a lot to talk about in it. I felt the angle I wanted to talk about was the castle they built together, which is really more of a stately home on the edge of Trieste.

I hadn't visited Trieste at the time that I was writing the lyrics so I was doing searches online to get photographs. When I did visit, when we were recording the album, I had already written the lyrics, and I was quite pleased to see that I had got things mostly right, and I think we tell the story well. The music is very dramatic in places, as it needs to be. We've released a slightly edited version of it as a single, but I think that's gonna be good fun to play live at some stage.

One of the things that that stood out for me about that track was the group's vocal harmony attack. It felt like all of the vocalists in the band got involved, and it was really dynamic.

I was able to watch them do that. They set these vocal booths up in the studio—it was a little bit like the Spinal Tap thing where they try to come out of those little pods, but they were all allowed out at the end. [laughter]

So I saw that done in real time. It's an amazing thing to listen to. It's gonna be hard to deliver live because one of the problems with rock music on stage is monitoring. As long as you can hear yourself and others, then you can sing in tune. Often when you hear singers singing out of tune, it's just because they can't hear themselves. It's a really hard environment to get right.

When we're playing live we have a separate monitoring engineer, because it's really important that we've got our communication with that guy and that when we’re randomly pointing at something he knows what to do. I'm looking forward to that and—since according to Rob [BBT soundman extraordinaire Rob Aubrey] I’m not allowed to sing, they get all they want of my voice on my demos—I shall sit back and watch in amazement as they deliver that live, and not have to worry about it. [laughter]

Moving down the track list, “Love Is The Light” struck me as kind of a grand hymn. It's widescreen in scope, but also contemplative.

It is. That’s a song of Alberto's. “Miramare” was written specifically for the album, but “Love Is The Light” was written probably three or four years ago, so not for Big Big Train. When we started talking about whether he wrote, Alby said “I've got some songs and have a listen to this one” and he'd obviously prepared the demo to arrange it as a Big Big Train song.

You should be able to deliver any good song in multiple different arrangements, and this one immediately spoke to my heart. I could hear the sentiment and asked him what it was about. It's a very personal story about a period of depression that Alberto went through. He had most of the lyrics, but asked me to work with him to get the lyrics finished off. So I had the pleasure of doing that and talking with him about what he wanted to get over.

We talked at the start of that conversation about how I had managed, how it was friendship and love, and that was what pulled him back, too. He could see that his lovely wife was there for him, and his friends, and it's the little glint of love that was able to bring him out of those fairly dark times. It just hit him out the blue, this depression, he wasn’t responding to grief or something. It just took him completely by surprise, as it does sometimes. And I did say to him, “This is very personal, are you sure?” But he was. When it comes to it, we need to share these experiences, because I think they can help others and they can speak broadly about the human condition.

As with “Oblivion,” it's a song we've already debuted live and the other day, in a different interview, Alby said that the first time we played it, it was quite a big moment for him—“Oh, this is one of mine.” He was playing a show as the frontman for Big Big Train, but also, his material was being performed by the band.

The other thing that was nice, even in the demo, was a little hook in there, a call and response thing where I immediately thought, “That's going to work with an audience,” and sure enough it has done. It is the most beautiful moment when you're playing live, when the audience and the band become one. You're all there together and all enjoying the performance and you're part of it as well. It was a little bit emotional seeing that unfurl during the tour, as people became more aware of the song.

It feels like there's a true story behind “Bookmarks,” and I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that song.

Yeah. This was, again, back to Sutton Coldfield and my childhood. I had a gang—not a bad gang, just a gang of boys and girls where we were out riding our bikes together all the time. Back in the ’70s there were fewer cars around and it felt a bit safer and we were like a free-range clan. And then things gradually began to fall apart as we grew into teenage years. One person moved away and another person maybe got a girlfriend and started to lose interest. So I was thinking about that moment when you knocked on the door to go out with your gang, and one day the person said “No, I'm not coming out today.” And I thought about how at some stage that close-knit gang of friends rode out together on their bikes for the very last time, and you didn't know that that was the last time you would be together. And it was quite a big moment in your life, when you look back on it.

I was thinking about it in those terms because it happened that these friends were some of the ones that really helped me deal with both the loss of David and the loss of my stepfather. So it felt like my kind of wing-men and women had come back around, and it became a very romantic sort of vision of these people reappearing on their bikes, almost like the gang getting back together, just to support me. But that's how it was, and I tried very hard in “Bookmarks” to talk about it. It's the only song on the album that directly mentions the passing of David because it was like a shocking “storm in the night,” as I described it. And when everything seemed to fall apart, then friends came round to offer support. It's quite heartfelt. I hope people find something in it.

It was nice for me when we recorded it because the first half of the song’s just 12-string guitar and piano, and that was just me and Alberto, we did that together live. It was really good to feel that there was a new friendship happening there as well when we were recording it. It’s maybe “Curator Of Butterflies” sort of territory for Big Big Train—not a ballad per se, but just a song that hopefully people will connect with

As you were describing the group riding out, I was seeing the artwork for the album.

Yeah, that was it. I had shared all the demos with Sarah [artist Sarah Louise Ewing, who has provided the cover art for a number of BBT releases], and that was the last thing. I didn't really give her a steer, just “Here's the words to the whole album. Here's all the music. Go and have a listen. See what speaks to your heart.” And that was what she came back with, she wanted to get that sense of comradeship of that childhood gang, the essence of it, just running across the fields. She came back and said “I want to do that,” and I said “Yeah, that's good for me.”

“Last Eleven” is a song about school days and a group of friends and peers who weren't part of the athletically gifted crowd. It feels very much in character for Big Big Train in terms of shining a spotlight on people who've maybe undeservedly escaped it.

Yeah, that was it. It's a bit of a cliché, but it's saying that we all have value and we all bring something to humanity. It was celebrating the late achievers or the people that maybe don't shine at school or other things. And it's a true story. I'm a skinny six-foot-two guy, and when I was at school I was a very skinny six-foot-two lad. I did not look sporty at all. I was a quick sprinter, but otherwise people just thought “He’s an airhead.” [laughter] ’Cause I was a bit of a dreamy kid.

The school is an old-fashioned grammar school, like maybe 600 years old, with real traditions. They felt nothing wrong at the time that you'd select your cricket team for the summer term and that the kids at the end that were not selected, were just called extras and were put into these two teams for, literally, the leftovers, called Extra 1 and Extra 2. And I was an Extra 2, so I was below the bottom of the pile. But I did have this secret skill of being a fast bowler. And so I would find myself—and it happened several times—where I was in a duel with these kind of big sporty guys and I would bowl them out. I would clean bowl them. [American readers: think “strike out the cleanup hitter.”]

You're American and so cricket may not mean too much for you, but when you put a ball through and you take a middle wicket, it's a big moment in your life. It certainly was for me as a child and it just felt like, the rock kids, the geeky kids on this extras team, one of us would hit a six, I'd get a clean bowl on somebody and it would just feel like a way of the uncool kids coming together and finding their own way forward with the right friends and stuff.

So it's a celebration of that. It's “Never fear there are other people out there for you. If you find them, there's hope and you can enjoy life.” It's a celebration of those kids, of which I was definitely one.

At 65 minutes, the album is packed with new music and it feels like the new lineup has hit its stride very quickly in terms of composition. There are also more co-writes on the new album than has typically been the case for Big Big Train. Did you find co-writing particularly rewarding this time around?

Yeah, I did. I think one of the mistakes David and I made over the years was that we ended up writing together less and less rather than more and more. David was an interesting character, because he was primarily a solo artist, really, who ended up in a band. And I think he had to work against his instincts a lot of the time, though I think he grew to love being in Big Big Train. But it must have been difficult for him, and not long before he passed away he had time to work on his solo albums.

It was interesting when I went back through some emails. When David joined Big Big Train, he had no means of recording or finishing things. We'd created our own entity to make and release albums [English Electric Recordings], so when he joined the band, the deal he made with us was “I’ll work on The Underfall Yard for you and then you can guys can help me finish and release my solo album that I've been wanting to make.” Which ended up 10 years or more later because, bless him, David put that aside to run with Big Big Train. I'll always be very grateful to him for that. But I think the gravitational pull of his solo stuff was always kind of there, and as time went on we did write less and less together, which was a shame.

For this album, instinctively I was thinking “There are no rules now. Let's just see what happens.” And so yeah, Alberto and I have created quite a strong songwriting partnership, and I'm sure that will continue going forward. And I've been writing with NDV, and Dave and NDV were writing together and stuff. And Rikard—you know, we're already working on the beginnings of the next album and Rikard’s already written… not a short piece. [laughter] And I will be working on that with him and Alberto as a co-write.

For me, everything changed, and so if everything changes, you just have to roll with it and see what happens. We've just gone with it and I've enjoyed it very much.

On the new album I feel like in musical terms, you can feel the players flexing their muscles a bit and I wonder how much of that is just a natural evolution as new musical personalities enter the mix and how much this reflects a consciousness that this is the beginning of a new phase for the band.

Yeah, I think everyone wants to make their mark. And we're not running away from that prog rock thing either, you know, where a certain level of playing is expected as part of the territory. The most important thing is to get the emotions into the recording, of course, but also, prog rock can be fun. You can have a lot of fun by producing music that will just make you go “Wow!” and I think all the players in the band wanted to spread their wings a bit and let the music take flight. If people enjoy extended instrumental sections and complex passages, I think there's plenty of that on there for people to take away alongside, hopefully, the melodies and lyrics.

That's the thing with prog rock, it's a beautiful way of expressing yourself because it frees you from three-minute songs. It frees you from the expectation of easy hooks and all that and enables you to think in terms of an audience that will want to listen to things in depth. I'm not being snobbish about it; I really like good pop music, but I think prog rock allows you to take flight.

I would also say that, on this album, we were not prepared to let anything not be as we wanted it to be. Over the COVID years we found ourselves having to make albums that we almost hadn't quite got right in our heads. This one was never going to be like that, because this is the first release with Alberto as the lead singer, the first proper new release after David passed away, and the first with Oskar. Very much of a new thing for us, and it had to be as good as we could do at this point in time.

I'm beginning to see some reviews and for the most part, it feels like people are getting it. When David passed away and we decided to carry on, we did think about what's happened with other bands—and there aren’t that many—who’ve been in this sort of situation. You think of a band like The Doors, where nothing was the same. You think of a band like AC/DC, where they were able to kind of reinvent themselves. We knew it was a bit of a long shot, but at the moment it feels like people realise that we've at least put our heart and souls into this.

Around the time that the 2010s version of the band came together, you shifted from playing guitar and occasional keyboards to playing bass and occasional guitar. Ever since then, it feels like your bass playing has grown progressively more confident and adventurous, and there are moments on The Likes Of Us where you're almost playing “lead bass” like a Chris Squire or Geddy Lee. And I just wanted to ask, who are your favorite bass players? Both the ones you enjoy listening to and the ones whose style you gravitate towards as a player.

If you talk about progressive rock bass players, people generally mention Chris Squire first and foremost. I find the Yes rhythm section really interesting because it generally had the drummer doing one thing and the bass player doing something else—a really interesting approach, but sometimes you think, “Crikey, they're almost playing different songs!” [laughter]

For me it was always Mike Rutherford. Genesis was completely different from Yes, you had Mike and Phil [Collins] very locked in together. Mike was certainly up there technically, but maybe less showy, and of course he was doing bass pedals and 12-strings as well, all of which I’ve got now, the double neck and all that stuff. Unquestionably Mike Rutherford from the ’70s and early ’80s is my biggest influence as a bass player.

John Wetton I think was an amazing bass player, really musical. He had that almost church music background, I think, which comes out in some of his composition, but then he had that brutal, almost demonic bass sound, overdriven, massive cab, just amazing.

If I'm watching a band, quite often I’ll zoom in on the bass player, I saw Ben Folds recently and his bass player for his UK tour, Mandy Clarke, was really good. It’s not just the prog side of things, in all types of music, when I can hear someone whose playing speaks to me, it will seep into the musical DNA. The bass player back in Ben Folds Five was great, too—again, really interesting.

Robert Sledge.

Yeah, he’s really cool. The interesting thing with Ben Folds is, of course, he’s doing quite a lot on the left hand on piano. With Big Big Train I find sometimes that the pianist is going to town over here [on the left / bass end of the keyboard] and I'm thinking, well, what do I do? Because you're taking up all of the octave there! Sometimes you do have to come up the neck and just sort of get out of the way of what other people are doing.

Coming back to your original point, I feel way happier on the bass now than in years past. I've played a lot of gigs now. It's been a slow process for me, but I do feel quite confident as a bass player and more happy to go up the dusty end and do different things.

Oh—McCartney! [laughter] Another amazing player who was able to deliver both the rhythmic content, working with the drummer, but also add some melodic interest as well. That’s what the best bass players do, and that's what I try to deliver if I can.

One of the things that fans I think enjoy and admire about Big Big Train is that you all seem to enjoy one another, both musically and personally. That seems as true of the current lineup as of past ones, and I wondered if you might share a favorite story or two about your bandmates.

Honestly, the time we had on the tour bus last year was just an absolute riot. A tour bus is a very interesting environment. In Geddy Lee's book, he calls them shelf people because you're sleeping on a shelf, effectively. I won't mention names, but I know some musicians that just can't get on with their bandmates in the close confines of the tour bus, and it gets very difficult.

It's completely the opposite for us. It's got to the stage now where if we're told we're doing shows without a tour bus, it’s like [disappointed] “Really?” After playing a show you might imagine that you want to go back to a nice hotel bedroom, but in fact what you want to do is to go and decompress, and the guys and girls you want to do that with are the people you've just been on stage with. We have an absolutely great time, we play music and tell stories and dance, all of those things. I probably can't share more—you know, what goes on the tour bus stays on the tour bus—but I know there is footage of me dancing, which will inevitably escape at some stage. [laughter]

All I can say is, it's a blast. It's where the band’s “brothers and sisters” thing really does come to pass and it's good. We're on the tour bus in the States. It was 50/50 if we were gonna have a tour bus or just do hotels and the decision’s been made that the tour bus is happening. So we were like “Yay! We get some time together.”

You've built an audience from scratch as a fully independent band and then built a robust presence on Facebook and the web. But there have been some significant developments in that department recently: first the group signed with Inside Out and then Bandcamp was sold and lost half their staff, and that's a major platform for many bands. What are your current thoughts on how BBT is navigating what seem to be continually choppy waters in the music industry?

Over the last three or four years we’ve tended to think “Okay, we've hit the glass ceiling here.” There are a handful of artists—not in the prog world—that, maybe they get a TikTok hit or something. On TV the other day there was a really lovely guy doing a sort of pop-soul thing, who had taken off on TikTok and now he’s playing arenas. There are always going to be the odd ones that just manage to crash through without record company support.

But I think we've been doing it for so long that we're just kind of stuck here, in a kind of waiting room of not quite making it to a bigger audience. And that's all we want, really, is to be able to sustain ourselves financially, and most importantly for our songs to be heard by as many people as possible. So we've been thinking for a while about signing a deal. We were lucky enough to be in a position where we almost had a bit of a beauty parade going on. I think people look at us and think “Kind of a traditional-sounding prog rock band. There aren't many of those around, apart from the original ones from the ’70s or ’80s.” So there's a bit of interest around our sound being slightly unique these days.

When David passed away, to be honest, I wasn't sure whether or not that would be the end of things. For example our booking agent, United Talent, decided to stop working with us. And I don't blame anybody for that—it's a business at the end of the day. But Inside Out were brilliant and they stuck with us and so all my fears of signing to a label over the years and losing control, none of that's happened. I've found myself working with a label where the A&R people and the managers that we know are just great. They've been incredibly supportive.

The economics behind it are still not great for bands. The big labels have a significant ownership stake in a lot of the streaming sites, so it's still difficult to make your way, but we do feel we've got label support. And I'm not one of those sorts of King Canute-like characters that tries to pretend that streaming is going to go away. We've got a Blu-ray coming out later this year and how many more Blu-rays are we actually going to be able to release? Again, the label is behind us on that, but the physical market is tough, apart from the weird vinyl rebirth and CDs beginning to level off.

It's really, really hard and not everybody can make a career out of playing live. That seemed to be the answer at some stage—“Oh, go down the live route.” But that's really hard, too. We're doing an autumn tour in the UK and that just went on sale, so immediately our management are looking at the numbers. How many tickets have we sold? Because you get a feel early on. Are we gonna be able to sell these shows out? Or how much money are we gonna lose this time? Touring, we've always lost money. And we need to find a way of not losing money.

I'm realistic. I don't think the world owes us or anybody else a living. But I'm also optimistic because I think we've now got a very good record label who have our interests at heart. The Japanese side of Inside Out, Sony Music in Japan, they've gotten foursquare behind the new release. I wasn't expecting that. So the album is going out with full translation and all of that sort of thing. I'm not one of those people that gets angry about the world as I wish it would be. I accept it as it is and try and roll with it.

Sometimes I think that's all you can do.

It is! I think you've got to accept that there are some good things about the modern world of music and be happy about those things whilst accepting that it's never gonna be perfect. And it's a commercial world at the end of the day, isn't it? It's “money talks and bullshit walks,” as they say in Spinal Tap. At the end of the day that's still true.

That great fount of wisdom, Spinal Tap.

Indeed, it continues to be and will always be so. And in fact they're talking about making a new one, and I pray they get it right and don't besmirch the treasure that is Spinal Tap. Please let it follow on and be a good thing. Fingers crossed.

One last question. You co-founded Big Big Train in 1990. It's been a long and unpredictable road since then. Knowing what you know now, if you could whisper in the ear of your younger self back then, what advice would you offer him?

[laughter, followed by a considerable pause] The advice that I would offer myself would be advice that I've tried to share privately with others: surround yourself with talented people. It’s easier said than done, and sometimes you need a bit of luck to find those talented people, as we have had. But it can make all the difference.

My main role in Big Big Train has been as a songwriter, but I can't sing, and I'm not a virtuoso guitar player. So I can't break out of my own confines; I've required other people to help me, to sing and perform and do things that I can't do. If you're lucky, just surround yourself with talent, and that will help your own talent come to the surface.

[Chuckling] The other thing I would whisper in my ear is, “Don't do it!” [laughter] Because what a mad road it’s been. Notwithstanding the recent tragedies that we've been through. Back at the start, it was just me and Andy [Poole, co-founder of the group] and then we got some band members together and we played some gigs locally and then it all fell apart. So we just started doing music at home, in our own studio. And then David came into our lives, and Nick, and Rikard, and suddenly the kind of Pinocchio story started to happen to us, you know, the puppet became a real band! And we were playing gigs!

I still remember walking out on that stage [at King’s Place, London] in 2015 for the first shows that we did with David. I hadn't played live for so long. And then walking out on the stage and being met with this, just, roar that almost lifted us off our feet. And everything since then, being able to quit work and starting to tour around the UK and in other countries… it’s been bizarre, a very strange thing.

I suppose my other advice would be, “You never know what's around the corner.” That can be bad and it can be good. I've had both of those things happen to me, but if you've got belief that what you have to offer is a positive thing, then just stick at it. Sometimes the tortoise wins.

#

[Many thanks to Gregory for his time and candor. As an endnote, this is the longest interview The Daily Vault has ever run, but at a certain point in the process we elected to emulate our interview subject and declare “Oh! It’s one of those.”]