Features

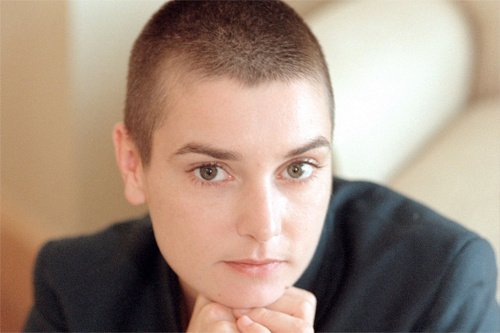

Sinead O'Connor: A True Pop Maverick

by Peter Piatkowski

Sinéad O’Connor has died, leaving one of pop music’s most divisive and challenging legacies. An unequivocal talent, O’Connor weaved politics, social critique, and activism into her formidable career, often risking her lofty popularity by embracing issues or putting out statements that would prove to be controversial. Throughout the noise of her confrontational image, O’Connor possessed one of the most beautiful voices in pop music: she had a pure, powerful tone, able to stab listeners with the pain manifested in her preternaturally gorgeous instrument.

Sinéad O’Connor has died, leaving one of pop music’s most divisive and challenging legacies. An unequivocal talent, O’Connor weaved politics, social critique, and activism into her formidable career, often risking her lofty popularity by embracing issues or putting out statements that would prove to be controversial. Throughout the noise of her confrontational image, O’Connor possessed one of the most beautiful voices in pop music: she had a pure, powerful tone, able to stab listeners with the pain manifested in her preternaturally gorgeous instrument.

Like most women in the public eye, she endured reductive, sexist media and press outlets seeking to minimize, label, or categorize her. She was slotted into facile brands like “angry” or “rebellious.” The mainstream press took issue with her statements, her refusal to play the part of the pop diva, and her shaved head and eschewing of pop glamour. Her idiosyncratic and unique approach to celebrity and stardom confounded, confused, and discomforted.

But beyond all of these critical but vestigial details is the music. Sinéad O’Connor’s incredible discography includes some of her generation’s most creative and exciting pop. Her albums The Lion and the Cobra (1987), and I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got (1990) are among the greatest studio LPs of the 20th century. Her debut is a thrilling exercise in pop experimentation as O’Connor weaves different sounds, testing the limits of mainstream pop/rock. She looks to college rock, art rock, dance, dance-rock, and pop while crafting one of the most explosive introductions to music audiences. It’s a debut record that avoids cheap sentiment or crass and trendy productions, allowing it to age gracefully. Singles like "Troy" and "Mandinka" are dramatic, emotional, and practically cinematic. Though she was only twenty at the time of the single’s recording, "Troy" showcases a startlingly mature and self-possessed artist, her gigantic voice—a beseeching howl, really—reflecting a deep well of emotion and pain, the kind of experienced life typically heard in the guttural growls of a wizened blues shouter. Over pulsing, ghostly synths, O’Connor’s voice, ragged with emotion, cuts through like a scythe.

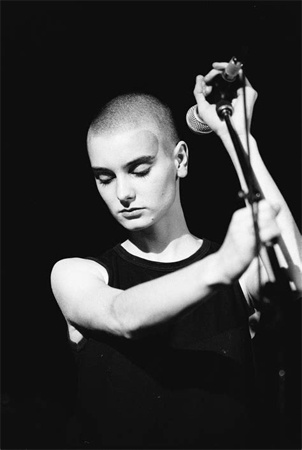

Predictably, O’Connor will be remembered by most for her scorching cover of Prince’s “Nothing Compares 2 U.” With co-producer Nellee Hooper, O’Connor took the song and transformed it from a pleasant pop ballad into an elegiac dirge. The production is relatively lean: a mournful synth mews as O’Connor’s heartbreaking voice echoes. “Nothing Compares 2 U” is a love song; more accurately, it’s a song about lost love. O’Connor’s intense work imparts an urgency and desperation wholly her own.

“Nothing Compares 2 U” made Sinéad O’Connor into a reluctant pop star. The single shot to number one on the pop charts. Its stark video, directed by John Maybury, became one of the most indelible images on MTV—an unforgiving, unrelenting closeup of O’Connor’s perfect beauty as she performs the ballad with such power she moves herself to tears.

The song and the video overwhelmed its parent album and the other singles; “Nothing Compares 2 U” would cast a long, looming shadow over everything O’Connor would do in her career. Though she recorded vibrant albums throughout the 1990s and into the 2010s, the massive success of “Nothing Compares 2 U” feels like a premature end, the closing of a chapter of a book that ends far too soon.

Because of her commercial success, O’Connor’s public pronouncements, statements, and acts became fodder for the tabloid press, which profoundly misunderstood her. She refused to perform in venues that played the American national anthem. She snubbed the Grammys. In October 1992, when appearing on Saturday Night Live, in an act of protest, she tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II after a particularly scorching version of Bob Marley’s “War.” Her motivation was the Catholic Church’s sexual abuse of children, particularly the institutional coverups initiated by the Vatican. Ahead of her time, O’Connor waged war against hypocrisy and sexual abuse, facing a formidable opponent. Even fellow firebrand Madonna mocked O’Connor’s sincere and important advocacy with her appearance on SNL, tearing a photograph of Joey Buttafuoco. (Madonna’s questionable swiping at O’Connor is particularly disappointing given that she herself has been a target of a sexist and narrow-minded press.)

The backlash was swift and devastating. When appearing at a Bob Dylan tribute concert at Madison Square Garden, O’Connor was booed and heckled by the audience. Kris Kristofferson proved to be an ally, joining, embracing, and encouraging her. (Kristofferson paid tribute to O’Connor with his touching ballad “Sister Sinead” for his 2009 album Closer to the Bone.) O’Connor became a target for conservatives and late-night comedians. Frank Sinatra threatened her with assault.

The backlash was swift and devastating. When appearing at a Bob Dylan tribute concert at Madison Square Garden, O’Connor was booed and heckled by the audience. Kris Kristofferson proved to be an ally, joining, embracing, and encouraging her. (Kristofferson paid tribute to O’Connor with his touching ballad “Sister Sinead” for his 2009 album Closer to the Bone.) O’Connor became a target for conservatives and late-night comedians. Frank Sinatra threatened her with assault.

As the noise of her activism continued, she quietly released Am I Not Your Girl? in 1992. A surprising collection of pop standards, torch songs, and Broadway showtunes, the record wasn’t well-received by audiences or critics. It seems like the record was a deliberate attempt to stave off the growing pop superstardom she was gaining with “Nothing Compares 2 U.” The record’s content was a seeming attempt to showcase O’Connor as a singer, creating a distance between the vocalist and the songwriter. The album deserves a reevaluation as it contains some of her most affecting and moving performances—for example, she manages to make the banal “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” into a hushed, bruised lullaby.

After the muted reception of Am I Not Your Girl?, O’Connor released the modern rock album Universal Mother (1994). Featuring the bracing, deep single “Fire On Babylon,” which charts O’Connor’s difficult relationship with her mother, Universal Mother worked to build on the artistic success of her first two albums. It contains some of her most personal poetry and impassioned wailing. An early proponent of hip-hop and funk, O’Connor includes Black American pop sounds into the record, including the confrontational “Famine,” in which the singer lectures her listeners on the history of Ireland and the story of the Great Famine. A jazzy, rap-influenced tune with shades of trip-hop and house, “Famine” is one of O’Connor’s most essential tracks. The album’s first single, “Thank You For Hearing Me,” is another track that looks to hip-hop and electronic sounds as it chugs gently over a thick, undulating beat.

After the muted response of Universal Mother failed to return O’Connor to the heady heights of the pop charts, she spent the rest of the 1990s putting in guest appearances on albums and tribute concerts, putting out an EP in 1997, and performing live. Her comeback studio LP, 2000’s Faith And Courage, continued with her affection for Black American pop, featuring collaborations with Kevin “She’kspere” Briggs (TLC, Destiny’s Child, Mariah Carey, P!nk), Jerry “Wonda” Duplessis (the Fugees, LL Cool J, Whitney Houston), Sugarhill Records alumnus Little Axe, and Fugees superstar Wyclef Jean. The album captured some of the slick urban pop of the millennium, especially in her work with Wyclef Jean, like the swirling pop tune “Dancing Lessons” or the reggae-pop of “The Lamb’s Book of Life” with Briggs. She also teams up with the Eurythmics’ Dave Stewart on several tracks that lend the album the expansive, synth-heavy sound of his work with Annie Lennox. Faith And Courage is aptly named because it finds that sweet spot in the intersection of 2000s mainstream radio pop and O’Connor’s intensely personal songwriting and unique vocalizing. Faith And Courage garnered warm critical notice like its predecessors but didn’t set the charts afire.

It seems that Faith And Courage was O’Connor’s last attempt at making radio-friendly pop music. Her output for the rest of her career would be dominated by niche and esoteric projects, including the brilliant 2002 album Sean-Nós Nua, a collection of traditional Irish art and folk songs; Throw Down Your Arms, a thoughtful tribute to classic reggae; the sprawling two-disc Theology; and her last pair of rock albums, 2012’s How About I Be Me (And You Be You)? and 2014’s I’m Not Bossy, I’m The Boss.

O’Connor’s story isn’t one of diminishing returns. It’s true that after I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got, her albums were no longer big sellers. Still, O’Connor quickly established herself as a legacy artist, too stylized and individualistic to maintain a long mainstream pop career. She sought her muses and musical inspirations, mining obscure and abstract musical sounds and genres, mixing mainstream pop with traditional, folk, and art songs from Ireland, Africa, and the Caribbean. An early advocate for hip-hop, she collaborated with rap artists like legend MC Lyte on the 1988 single “I Want Your (Hands On Me)” and embraced club culture with dance remixes of her singles as well as recording with trip-hop masters like Massive Attack. Her musical output is a patchwork, a collage, or a tapestry of popular music of the latter half of the 20th century.

Because of her very public struggles with her personal life and mental health, much attention will be given to her turmoil. Of course, her art was informed by those struggles, so it would be disingenuous to try and focus on her work and eschew any talk of those problems. But she was so much more than just a troubled artist battling demons. She was an original, a woman who looked at how mainstream pop music sold music, sold musical artists, and sold women in the public eye, and tried to fight against all of that. An artist as complex and complicated as Sinéad O’Connor is also an artist of contradictions. Her one-woman battle against patriarchy, capitalism, child abuse and exploitation, and discrimination wouldn’t be linear, nor would it be free of seeming contradictions. But she was sincere and genuine in everything she did.