Features

Larry Lynch: The Daily Vault Interview

by Jason Warburg

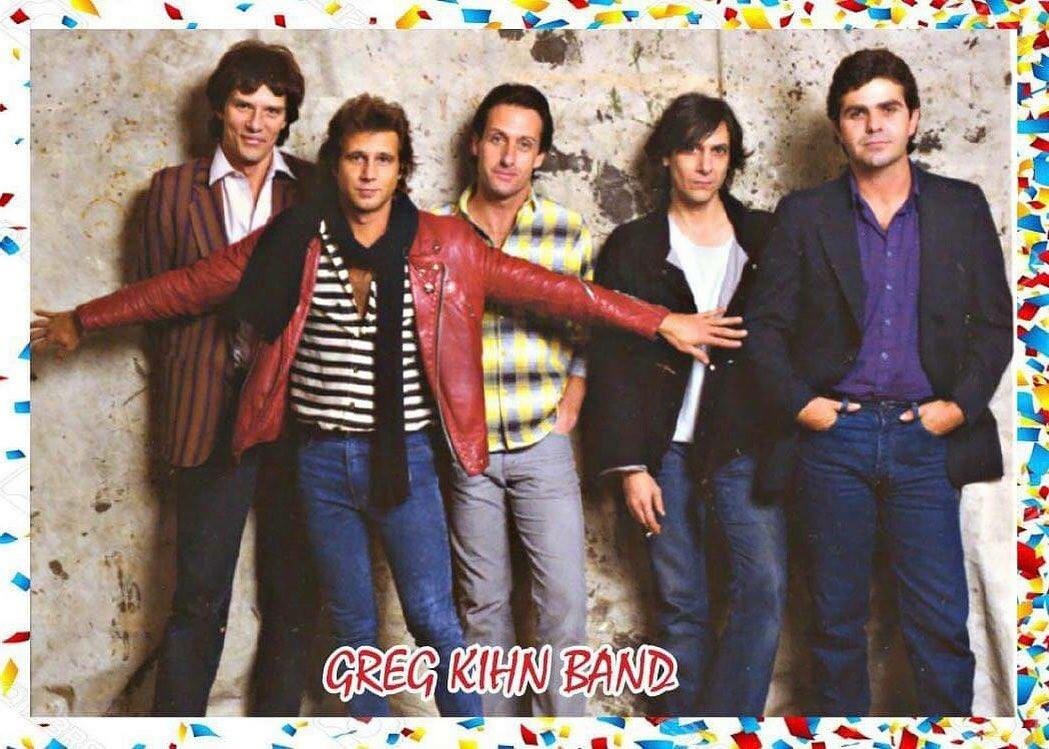

I saw the Greg Kihn Band no less than nine times in their 1980-83 heyday, rising with them from small clubs to opening slots in college auditoriums and then headlining those same venues. Though the band consistently delivered its Buddy Holly-inspired power pop with abundant energy, it was apparent from the first show I caught that one of these things was not like the others. Frontman Kihn, Steve Wright (bass / harmony vocals), Dave Carpender (guitar), and Gary Phillips (keyboards / guitar) played hard and hungry, their expressions generally intense. Meanwhile in the back, drummer, harmony vocalist, and occasional lead vocalist Larry Lynch seemed to be permanently “on,” a natural performer with an infectious smile.

The band came together in 1976 under the auspices of Beserkley Records, the East Bay home of Earth Quake, Jonathan Richman, and The Rubinoos, among others. With Kihn as the frontman and principal songwriter (often in collaboration with Wright), the band cranked out an album a year for nine straight years, building a local following while playing shows for Bill Graham, before eventually breaking regionally with 1981’s #16 hit “The Breakup Song (They Don’t Write ’Em)” and then nationally with 1983’s #2 smash “Jeopardy.”

Besides playing a key role in the band’s powerful harmony attack, Lynch also contributed several lead vocals along the way. With the Naked Eye (1978) featured Lynch singing his original tune “Can’t Have The Highs (Without The Lows),” Glass House Rock (1980) had him fronting a galloping take on the old Western theme song “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” and singing the break on a thrumming version of The Yardbirds’ “For Your Love,” and Kihntinued (1982) found him delivering a dynamite cover of the old Jackie Wilson hit “Higher And Higher.” As the keeper of the backbeat he also played a notable supporting role on “The Breakup Song,” whose prominent chorus drum hook is an underappreciated element of its appeal.

Lynch and Kihn parted ways at the height of the bell curve sketched by the latter’s career, with the albums that followed Lynch’s departure being credited solely to “Greg Kihn,” no “Band.” Meanwhile Lynch returned home to the Bay Area and began gigging locally as leader of his own group, working the special event and corporate circuit for more than three decades. More recently he’s formed a new group, The Faves, that includes longtime friend—and guest guitarist on Greg Kihn’s 1976 debut—Robbie Dunbar.

Our recent conversation with Larry Lynch covered a lot of ground, from buying his first drum set, to joining a band that moved from garages to clubs to theaters to festivals, to finding his way as a bandleader in his own right. If some of the lessons learned along the way were hard ones, they haven’t diminished Lynch’s passion for making music. Nearly fifty years down the road, singer, songwriter, drummer, and all-around performer Larry Lynch still loves to play, and does it with a smile.

The Daily Vault: Over the years I’ve seen so many shows by so many different performers, but I have never seen anyone bring more pure joy than you to the act of playing music for an audience. Watching you guys play made me smile every time.

Larry Lynch: That means a lot to me. There’s something that happens when I get on stage—I don’t know what it is, some people think I’m on speed or something because they say “You’re having such a good time.” I’m just giving it all I have. I’ve never taken drugs, but it’s like a drug in itself, getting up and playing music on stage. The feeling just takes over and it’s such a thrill to do that in front of so many people and make an impact on people’s lives. Performing live and making people smile makes me smile and makes me want to give more. That’s how it works.

When did you first realize music was going to be a big part of your life?

Probably when I bought my first Elvis record in about 1956. My dad took me down to the record store and I brought it home and started playing records and singing along. It was in my DNA somewhere and I got totally into Elvis. Every time I listened to his music, it just took me to a place, kind of like when I play. That’s what music does—if you’ve got problems, you don’t think about ’em, you’re just somewhere where you always feel good.

It started with Elvis and then I went on to buying all kinds of 45s and spending time at the record store. When I was 14, I asked my dad to help me buy my own drum set and he said “I won’t buy them for you, but I’ll give you fifty bucks to put down on them and then you make the payments.” And I said “Deal!” I had a paper route and every month I paid sixteen dollars on those drums from Sherman & Clay, a pink champagne set of Ludwigs.

Before then, I’d been going a friend’s house to play his drums. There’s a Beserkley Records album, The Spitballs, that was three Beserkley Records bands (Greg Kihn Band, Earth Quake, and The Rubinoos) all playing in the studio together—three drummers, three bass players and about six or seven guitar players. It was chaos, and everybody got to pick a classic song to go on the album. I picked “Gino Is A Coward” by Gino Washington and sang that one. It was really fun and everybody got the chance to do something different.

The reason I did “Gino Is A Coward” is that was the song I first learned how to play drums to at my friend’s house. He had that song and he’d let me play his drums and I’d sit down and I’d play that song over and over. I taught myself and got better and better and finally my friend said “Hey, I’m kind of getting tired of you comin’ over every day and playin’ my drums, why don’t you go get your own!” (laughter) That’s where it all started.

What were you doing musically before you connected with Greg Kihn and how did you end up joining the band?

I was playing with Steve Wright in a band called Passenger. We were writing our own songs; we both had the dream of writing music and being rock stars. Then one day I found out Steve was moonlighting behind my back, getting involved with the Greg Kihn situation. He had found out Greg had management and they were paying a salary—125 bucks a week! That was a big deal for Steve. He kept quiet about it at first, but then he told me and said they were looking for a drummer and asked if I wanted to try out. And I said “Heck yeah!”

So I went down, tried out, and got the job. That’s how the band started, Steve and I and Greg were playing, and then we brought in Robbie Dunbar, who was with [Beserkley label-mates] Earth Quake, and Robbie was instrumental in helping getting that first album [1976’s Greg Kihn] off the ground, and played on a couple of tracks on the second album [1977’s Greg Kihn Again] too. At that point he had to choose between the two bands, and he decided to go back to Earth Quake, which was the first band on Beserkley when the label started.

Then we picked up Dave Carpender and started really getting rolling, playing all the time. If we weren’t out on the road, we were back home cutting the next album. Greg was doing a lot of writing and we’d all get in the garage and start playing along to his ideas and that’s how all those songs were born.

Greg Kihn Band 1978: Steve Wright, Dave Carpender, Greg Kihn, Larry Lynch

Do you have any favorite stories from those early days?

Other than weekends, when we were usually playing shows, we rehearsed almost every day at a rented space down in Berkeley. This was back when there were no regulations and Beserkley rented out a couple of those big storage units and we turned it into a rehearsal space. We’d be down there playing all day and working on the songs, alternating rehearsal times with Earth Quake.

We did a lot of playing locally in the Bay Area and started doing a lot of shows with Bill Graham. Those were important experiences for us. We had only been together about a year when we got the opportunity to play Winterland for Bill Graham. It was the Greg Kihn Band and Earth Quake opening the New Year’s Eve 1976 show for Y&T and Montrose. We didn’t even know we were being filmed, but you can find that show on YouTube. It was just a thrill, a dream come true to be playing Winterland. We were beside ourselves, having such a good time, and we just kept playing locally and getting more and more fans as we went along. Every time we recorded an album we got better at that, and then we’d go out and play it live and get better at performing. The momentum kept building and it just got bigger and bigger.

Were there any songs from those early days that you were surprised didn’t become hits?

On the first album, I always liked “Any Other Woman”; they did put that out and it got an award from a radio station in Roswell, New Mexico. That was a thrill for us when we were just starting out—we’ll take it! On the second album, I though the Springsteen cover, “For You,” was going to break us big. I thought that song was perfect. Even Springsteen was impressed by the way that one turned out, so I thought that was going to be our big break. It never made the charts, but it got a lot of FM airplay.

On the third album [1978’s Next Of Kihn], “Remember” was another one I thought was going to do something. Our distributor liked “Remember” but said it was too long—they wanted us to shorten it down to about three minutes for a single. In those days you couldn’t just edit the recording, it was too difficult, so we went in to rerecord it at Wally Heider Studios in San Francisco. But when we tried to rerecord it, it sounded nothing like the original; all the magic was in that original take. So that one kind of died on the vine; I always thought that was a great song that should have been a hit.

The other songs on that album, “Cold Hard Cash” and “Museum,” boy those were fun to play live. We were over in Europe a lot around then because there was more interest in us there than in the States at that point. We were over there for a while, playing lots of clubs and getting some momentum going, but we were tired of being away from home and we wanted to make it in America, so we came back and recorded the fourth album [With The Naked Eye].

The funny thing is, once we started getting a foothold here in America, England cooled off. Their tastes over in England are definitely different than in America. Music can be a hit in some places and a miss in others. It was a real interesting dynamic. We were glad to come back home to America.

On that fourth album, I felt we could have done a better job recording “Rendezvous” [the group’s second Springsteen cover]. That’s just my personal opinion, though when they sent it back to Bruce, they didn’t get a real favorable response from him either. I just don’t think we captured it the way we did “For You.”

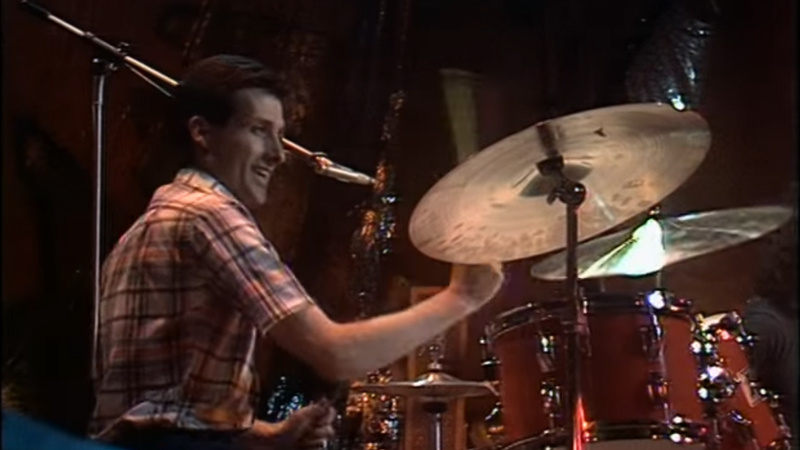

Larry Lynch on stage 1980

Another one that jumped out for me on that album was your first song recorded by the band, “Can’t Have the Highs (Without The Lows).”

I appreciate that. “Can’t Have The Highs” was my first song to make it onto an album. Every time we recorded, I wanted to get a song on the album, but the band was Greg’s thing and there was a lot of diplomacy going on. They finally let me have a song on the fourth album. There was never any discussion of putting that out as a single that I knew about, but it always went over well live—Dave Carpender played a wonderful solo on that song and it had a great ending.

That was pretty much it and we were heading on to the next album. Every time you put out an album, you’d immediately get out there and play to try to help promote the material you just released, and then you’d head back home, hunker down, write more songs and try to get lucky with the next album. It was a cycle we would go through over and over.

The fifth album, Glass House Rock, that one kind of fell on its face; it just didn’t have much that anybody was buzzing about as far as a single. But the next one, Rockihnroll [1981], had “The Breakup Song,” that they pushed as a single and it got up to number 16 and went over very well live. I loved that album. That was engineered and mixed by Don Cody, who did a wonderful job, and “The Breakup Song” moved us into position to get to the next level.

What was the reaction inside the band when “The Breakup Song” started to climb the charts and you guys started moving up to theaters and auditoriums?

It was a thrill to be playing bigger venues. We had worked ourselves up to a solid level, but that single gave us more credibility to get on some bills with bigger acts and get more exposure. And the more big shows you do, the better you get at them. We got more opportunities from that, but we were still slugging it out on the college circuit for the most part. Things didn’t break big until “Jeopardy” came out—that shot us to a whole other level.

In between Rockihnroll and Kihnspiracy, the album with “Jeopardy,” you guys released Kihntinued, with the cover you sang of “Higher and Higher.” What was the story behind the decision to record and release that?

“Higher And Higher” actually got some consideration for release as a single. It got some attention from the airlines—I remember flying and finding that on the list of songs to listen to! That really was a thrill for me. And then we played that song in Chicago, where the writers of that song [Gary Jackson, Raynard Miner, and Carl Smith] were there in the audience, and they told our management it was the best version they had ever heard of their song. That was such a high for me; I never got over that. That was just, “Wow!”

Singing that song always got a great response—I’ve always felt it was a good song for my voice and level of energy, and it just makes people feel good. It kind of checked off all the boxes and it was the high point of everything for me in the Greg Kihn Band.

"Higher And Higher" live 1981

As a fan, watching you guys up on stage and seeing how much fun you were having, it caught me by surprise when Dave Carpender left the band in 1983.

It caught me by surprise too. It was a decision made without my consent and I was not happy about it.

Dave was my roommate on the road for five years. He was one of the nicest, most genuine people I’d ever been with and I couldn’t have asked for a better roommate—we never had a bad day. When we were a four-piece on tour they would always double up the hotel rooms with Greg and Steve in one, and Dave and me in the other. When Gary Phillips joined the band [in 1981], we started having single rooms, but up until then, it was me and Dave.

Dave was a good guy who played his heart out and I loved his guitar playing. And then one day they made the decision to get Dave out of there and bring in Greg Douglass. It was just unfortunate. It was not a good day for me—I didn’t agree with that decision. Of course it’s all in hindsight now—Greg Douglass did an excellent job coming in and changing the dynamic. Who knows what would have happened otherwise?

When “Jeopardy” hit later in 1983 it blew the band up—you were all over radio and MTV and playing to the biggest crowds of your careers. What did that part of the whole experience feel like for you?

It felt like we made it, like this was it, the big time. Everything that you had hoped for was happening now, and it was overwhelmingly fun, but also a lot more stress, a lot more expectations and a lot more work. At the same time all that success was happening, people were changing under pressure and the tension started to increase. For one thing, all of a sudden money was rolling in and the money was not being distributed evenly. That created a wedge and made things inside the band less fun. Still, I was very grateful and excited that we had reached that level.

Greg Kihn Band 1983: Greg Douglass, Greg Kihn, Larry Lynch, Gary Phillips, Steve Wright

After the next album, Kihntagious [1984], was when you left. What made you feel like that was the right moment to move on?

It was a mutual thing. Basically I wasn’t having fun anymore, at least the kind of fun the rest of the guys wanted to have. I was the straight and narrow guy who lived a clean life and would drink milk and cookies and go to bed, and I wasn’t fitting into “the club” anymore. It was making it difficult for me to feel comfortable in the band and I was starting to feel like a misfit. I could tell they were getting tired of me—they started to call me “Father Larry” on the road. We all took the job seriously, but we had different ideas about what “having fun” offstage looked like. In the end they were glad to see me go and I was glad to go.

I don’t think there was even a meeting or anything, it was just one day someone told me I wasn’t in the band anymore. I don’t even remember how that conversation came about—it was just time, and that was the end of that.

Another part of my motivation was that I always wanted to be a singer and do my own thing. I wanted to get out there and see what I could do on my own, and that turned out to be a lot harder than I thought. I started playing locally and had a wedding band that was very successful for many years. We did well financially and didn’t have to fly all over the world, but it was a lot less glamorous and more humbling.

Any favorite stories from all the local gigs you played with your band over the years?

It’s a whole other dynamic. I had a lot of fun when we were a successful wedding band—I knew how to call the songs, perform, and get the audiences out there having a great time. We did that for 32 years, and for the first 20 it was fun, but after that it started to turn into a job, with more details to worry about, requests and things. Near the end it was starting to be more about the money and less about having fun, and I had to stop doing it.

That brought me to this latest situation. My old friend Robbie Dunbar was in the wedding band all those years with me, and we’re still having a great time playing together. Robbie and I have always done well writing songs and we’re doing that now with a new band called the Faves. We’ve got a couple of videos up on YouTube. One of them is a cover of “Remember,” the Greg Kihn song [see below]. The other one is an original Robbie and I wrote called “Never Ending” [see below] and we’re getting ready to work on a video of another song we just wrote called “Here Comes The Rain.”

At the same time, Robbie has resurrected Earth Quake and I’m playing with them, too. We were in the studio yesterday recording five songs, and that’s turning out to be a lot of fun—those guys are really rocking. Between the Faves and Earth Quake, Robbie and I are having more fun than ever and writing a lot of original material and it’s feeling exciting again.

“Here Comes The Rain” is an uplifting song about taking a very positive approach to being lonely: “Here comes the rain,” here comes the good stuff. It’s got a happy ending to it, and I’m excited about that song, so we’ll see what happens!

The Faves 2021: Robbie Dunbar, Larry Lynch, Jimmy Jet Spalding, David Tashinian

Before we wrap up, one technical question for you: what’s the key to singing and drumming at the same time?

Practice, practice, practice! (laughter)

Finally, imagine that, right now, you could whisper in your own ear back when you were just starting out in music. What advice would you give yourself?

The biggest lesson I’d share is to try to be more involved in the songwriting. With the Greg Kihn Band, because I wasn’t a songwriter on the hits, that created a big gap between who in the band was making money and who wasn’t. So I would tell myself, “You’ve got to be more involved in the songwriting, otherwise you’re not going to be as happy with the outcome.”

Other than that, I have no regrets with how I lived my life through those times. I’m healthy and I feel better than I’ve ever felt. I’m grateful that I took the road I did and I’ve still got a lot of energy and a lot more to do. Robbie’s kept himself in good shape too. We’re not unrealistic, we don’t expect to be rock stars, but it sure would be fun to make a good splash with these songs, coming from the heart and letting people know that it doesn’t matter how old you are, if it’s a good tune, it can still get out there and make an impact.

Faves - "Never Ending"

Faves - "Remember"